Byzantine Clergy: Patriarchs, Bishops, Monks, Ermits and holy men

The Byzantine clergy were key figures in the religious, political, and cultural life of the Byzantine Empire, serving as spiritual leaders, advisors, and administrators. From the Patriarch of Constantinople to the local parish priest, the clergy played a crucial role in shaping and preserving the Orthodox faith and the traditions of the Empire. They were also deeply involved in the many religious controversies that rocked the Empire, from the iconoclast controversy to the theological debates over the nature of Christ, and their positions and actions often had far-reaching political and social consequences. We will explore the various positions and people that made up the Byzantine clergy, and their impact on the history and legacy of the Byzantine Empire.

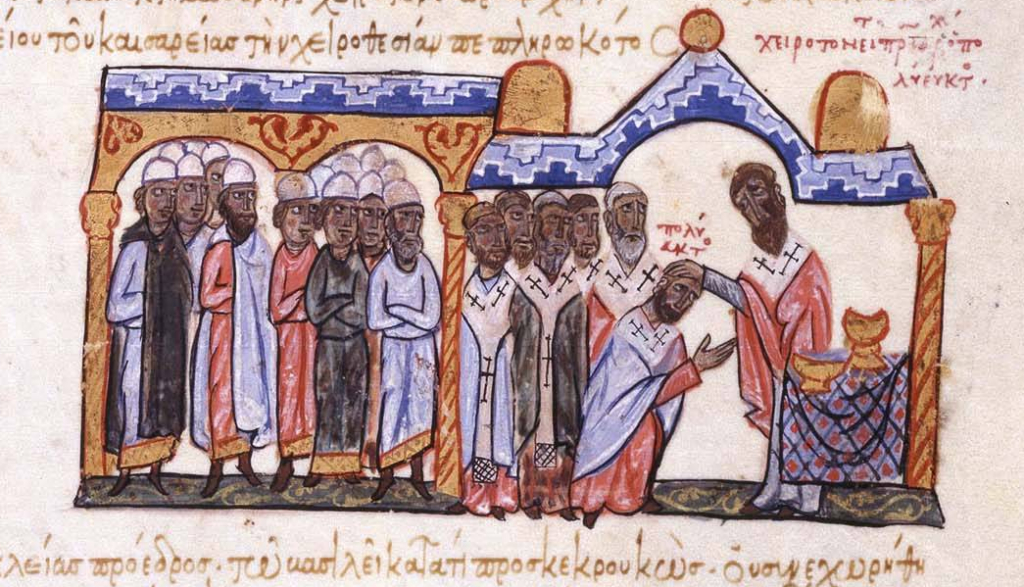

The Patriarch of Constantinople, head of the Byzantine Clergy.

From the obscure Bishop of Byzantium to the Patriarch of Constantinople.

In the beginning, the Bishop of Byzantium was a mere suffragan of the Metropolis of Heraclea of Thrace. However, the city’s refoundation as Constantinople and its subsequent elevation to the new imperial capital, coupled with the acceptance of Christianity, propelled its Bishop to the forefront. John I, who was appointed in 428, became the first Bishop of Constantinople to be bestowed with the title of Patriarch. This title was formally recognized by the Council of Chalcedon in 451, which established the Pentarchy, or the five great Sees of the Christian Church. Rome was ranked first, followed by Constantinople in second place, with the remaining three Sees being Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria.

While the importance of the patriarch was primarily attributed to its position as the capital of the empire, prestigious origins for the See were sought. Consequently, the tradition developed that Saint Andrew, one of the Apostles, had been the first Bishop of the Church of Byzantium.

The competition with Rome.

This situation created a competition between the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Pope of Rome. Although the Byzantines recognized an honorary preeminence for the See of Saint Peter, they could not conceive of the Church without the Empire. Consequently, they viewed Constantinople as the only truly ecumenical See, a perspective contested by the Popes. As Rome was under the jurisdiction of the Byzantine Empire until the 8th century, the competition remained relatively subdued.

However, the tension escalated in the following centuries, culminating in the Schism of 1054. Often refered to as the Great Schism, it marked the formal division between the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church. The split was rooted in longstanding theological, liturgical, and political differences, including disputes over papal authority, the insertion of the Filioque clause into the Nicene Creed by the Western Church, and varying practices in worship.

Tensions came to a head in 1054 when Cardinal Humbert, representing Pope Leo IX, placed a bull of excommunication on the altar of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, denouncing Patriarch Michael I Cerularius. In response, Cerularius excommunicated the papal delegation. While this dramatic exchange symbolized the schism, the division was not immediately irreversible but solidified over the following centuries due to further conflicts, particularly the Fourth Crusade’s sack of Constantinople in 1204.

In the last centuries of the Byzantine Empire, as the Ottoman threat loomed increasingly deadly, several Palaiologan emperors sought assistance from Western powers by advocating for the Union of the Churches. This controversial policy, aimed at bridging the schism between the Orthodox and Catholic Churches, faced strong internal opposition. The efforts culminated in the Second Council of Lyon in 1274 under Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, who formally proclaimed the Union. Michael VIII, who had recently recaptured Constantinople from the Latin Empire in 1261, sought to secure Western military support to defend his fragile empire.

However, the Union of the Churches was deeply unpopular among the Byzantine clergy, elite, and general population, who viewed it as a betrayal of Orthodox tradition. This resistance persisted despite Michael VIII’s efforts to enforce the Union, and upon his death in 1282, the policy collapsed. Subsequent emperors, including his successor Andronikos II Palaiologos, distanced themselves from the Union, signaling a return to Orthodoxy.

Later, as the Ottomans tightened their grip on Byzantine territories, Emperor John VIII Palaiologos revived the idea of Union, attending the Council of Ferrara-Florence in 1438–1439. There, the Union was again proclaimed, with the hope of securing Western aid. Yet, this attempt fared no better, as widespread rejection among the Byzantine population ensured it never took root.

The phrase “Better the turban than the cross” became emblematic of Byzantine sentiment, reflecting a preference for Ottoman rule over subjugation to the Catholic Church. This sentiment underscored the deep commitment to the independence of Orthodoxy, even in the face of the empire’s imminent collapse. Ultimately, these divisions left the empire isolated, culminating in the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 under Sultan Mehmed II.

The Patriarch as the Head of the Clergy.

The Epanagoge, one of the law codes of Basil I compiled circa 885, clearly states the Byzantine position: “The Patriarchal See of Constantinople, as illustrated by the Empire, has been elevated to the first rank by the decisions of the councils. Consequently, the sacred laws ordain that matters concerning other sees be submitted to the judgment and decision of the See of Constantinople.” The same code also stipulates: “The patriarch is the living image of Christ: his actions and his words express the truth.”

The Patriarch as a man of the Emperor.

The Patriarch of Constantinople was a major political actor, promoted by the emperor, but with the condition of controlling him. The choice of the Patriarch was therefore crucial. Theoretically, the patriarch is elected by the metropolitans and the suffragans of the patriarchate. The fiction of the elective system is maintained: when the seat is vacant, the permanent synod of Constantinople meets in Hagia Sophia. This synod is composed of the metropolitans present in the capital, but also of the highest dignitaries of the Church of Constantinople and of representatives of the emperor. Soon, it limits itself to drawing up a list of three names, among which the emperor chooses. In the rare case that the emperor’s candidate is not on the list, the Emperor can refuse it as many times as necessary.

Occasionally, the fiction is not even maintained, and several emperors have been arbitrarily appointing a patriarch. Cedrenus recounts that, on his deathbed, Basil II appointed and had Alexios of Stoudios enthroned on the same day, without consulting any ecclesiastical authority. In other cases, a close relative is elevated to the dignity: Theophylact Lecapenus, son of Emperor Romanos I, became Patriarch at the age of 16 and exercised part of his 23-year patriarchate while his father ruled the Empire. Anyone could be appointed: although it is theoretically forbidden, 13 laymen became Patriarch, among whom is Photios.

In the Byzantine conception, the Patriarch is almost a functionary like the others. The official nomination at the palace comes first and leaves no ambiguity: “The divine grace and my imperial majesty which results from it promote you, the very pious N…, patriarch of Constantinople.” Only after comes the episcopal consecration, delivered by three bishops including the metropolitan of Heraclea of Thrace.

Who were the Patriarchs?

In principle, the new Patriarch cannot already be a bishop, because the transfer from one episcopal seat to another is forbidden. The bishop is married to his church, his community. In fact, anyone could be appointed. Although it is theoretically forbidden, 13 laymen became Patriarch, among whom is Photios. In these cases, the nominee would receive in a few days, or even in one, all the ecclesiastical grades before being consecrated as Patriarch.

Indeed, until the 10th century, the emperors did not hesitate to choose for this post one of their close collaborators, a high official. This was the case with Tarasios, who re-established the images at the second council of Nicaea, of his successor Nikephoros, or of Photios. Sometimes, a close relative of the imperial family was elevated to the dignity: Stephen I was only 19 years old when he was appointed Patriarch by his brother Leo VI in 886, and Theophylact Lecapenus, son of Emperor Romanos I, became Patriarch at the age of 16 and exercised part of his 23-year patriarchate while his father ruled the Empire.

From the 13th century onward, the Patriarch is always a former monk. The latter have acquired a decisive importance in the Byzantine Church. However, the Patriarch is not in a more favorable position, and remains the right-hand man of the emperor. When the latter opposes the monks, for example, by moving closer to Rome, the Patriarch is forced to follow despite the monastic opposition that often pushed him to the patriarchal throne.

Power struggles and occasional conflicts with the Emperors.

However, the relationship between the Patriarchs and the Byzantine Emperors was complex and sometimes fraught. While often subject to the Emperor’s will, the Patriarchs were not always aligned with the imperial authority, and also had a duty to uphold the teachings and traditions of the Church. Sometimes, this led to conflicts with the sovereign. During the Iconoclast Controversy, the Patriarchs Germanus I and Nikephoros were iconophiles (in favor of icons) and resisted the Emperors Leo III and Constantine V’s efforts to suppress icons. In 906, Patriarch Nicholas I Mystikos opposed the marriage of Emperor Leo VI (886-912) to his fourth wife, Zoe Karbonopsina, as the Church’s canons forbade a man from marrying more than three times. During the late Byzantine era, Patriarchs opposed the idea of the Union of the Churches to end the Schism, going against the politics of several emperors of the time.

Nonetheless, the balance of power was rarely in favor of the Patriarchs. In case of conflict, the emperor always finds a compliant synod to depose the Patriarch, even if he is recalled a few years later. Through the permanent synod, the emperor also exercises a decisive influence in the choice of the holders of the episcopal and metropolitan seats, particularly the most important ones. The same is true for the designation of the Patriarchs, often virtual, but sometimes for Antioch under Byzantine domination, and for Jerusalem.

The organisation of the Patriarchate.

The cathedral seat of the Patriarch is the Great Church of Constantinople, Hagia Sophia, built by Emperor Justinian in the 6th century. It was located next to his palace, library, and a fully-fledged administration, similar to the Pope’s in Rome. This administration was led by a sort of prime minister, called a syncellus until the 11th century, and a chartophylax from the 12th century onwards. Belonging to this circle was almost necessary to reach the highest positions. Thus, of the 51 secular priests who became patriarchs, not less than 40 had been employed at Hagia Sophia.

The patriarch possesses the right of stavropegion, which means the privilege of founding any new church in any of the patriarchates. In his own jurisdiction, his court judges all cases involving clerics or those with religious significance, such as matrimonial disputes.

Metropolitan, archbishops and bishops.

Metropolitans, archbishops, and bishops constituted the secular ecclesiastical hierarchy of the Byzantine Church, all subordinated to the Patriarch of Constantinople. Metropolitans typically oversaw several bishops within their jurisdiction, known as suffragans. The number of suffragans and the relative ranking of metropolitans and bishops varied significantly throughout Byzantine history, influenced by the growth or decline of cities, ecclesiastical reorganizations, and the territorial expansion or contraction of the empire.

The title of archbishop was initially reserved for the bishops of the most significant sees in the empire: Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch. With the elevation of Constantinople and Jerusalem to patriarchal status in the 5th century, the title was used for the five leading bishops of the empire. Over time, as the title became associated with ecclesiastical independence or autonomy, it was also conferred upon autocephalous ecclesiastics, such as the primate of Cyprus (from 431), and the bishops of prominent cities like Ephesus, Thessaloniki, Athens, and Caesarea in Cappadocia. However, this distinction was not always consistently applied. Archbishops, particularly autocephalous ones, were not subordinate to any metropolitan but directly answered to a patriarch. These archbishops, often without suffragans, were numerous, ranked below metropolitans, and were elected by a synod under the patriarch’s authority.

The title of metropolitan denoted the head of the episcopate within a specific territory, usually corresponding to a civil province. This designation, first codified at the First Council of Nicaea in 325, derived from the metropolitan bishop’s residence in the capital (metropolis) of the province. By the 4th century, this Church administrative structure was fully developed and sanctioned by the council. The metropolitan held the exclusive right to confirm episcopal elections within their province, with the ordination performed by all the bishops of the region. Additionally, the metropolitan convened and presided over the provincial synod, held twice annually. However, the distinction between metropolitans and archbishops was sometimes blurred. Certain bishops without suffragans were granted the title of metropolitan, while metropolitans of prestigious sees such as Thessaloniki, Athens, or Ephesus were occasionally referred to as archbishops.

Each metropolitan, archbishop, or bishop had a cathedral church—usually the most prominent in the city—and a palace or mansion, along with an administration to manage the diocese. In Athens, the metropolitan resided in the Propylaia, while in Christianoupolis, a small settlement in the Peloponnese, the bishop’s mansion likely appeared as a fortified structure adjacent to the cathedral. Ecclesiastical properties, charitable institutions, and hospitals of the diocese were under the bishop’s control but managed by officials such as the oikonomos. Revenues came from property holdings, voluntary offerings, and donations, with additional income from ecclesiastical taxes like the kanonikon and kaniskion from the 11th century onward. These funds supported the bishop and clergy, as well as charitable activities, including aid for the sick and poor, the redemption of war prisoners, and church maintenance.

Despite their authority and privileges, Byzantine bishops did not generally assume feudal roles like their Western counterparts, although there were exceptions. Nonetheless, they wielded considerable political influence. In times of weak imperial administration, bishops occasionally took on leadership roles. A notable example is Michael Choniates, Metropolitan of Athens from 1182 to 1205. He denounced the corruption and greed of imperial officials in his appeals to the Constantinopolitan court and played a critical role in defending Athens against Leo Sgouros. During the siege, he led the city’s inhabitants in seeking refuge on the Acropolis, enduring heavy bombardments from siege engines. His steadfast defense of Athenian interests earned him a lasting legacy, and he was venerated as a saint in Attica soon after his death.

The vestments of bishops were similar to those worn by priests except, in later period, for the episcopal sakkos and omophorion.

On the fringes of the Byzantine clergy: ascetics, hermits, and other holy fools.

During the Byzantine era, especially at its beginning, many individuals were seeking spiritual excellence and striving to imitate the life of Christ. This often involved retreating from the world and leading an ascetic lifestyle.

Ascetics were individuals who sought to draw closer to God through lives of renunciation and personal discipline. They could live in monastic communities, but many preferred the solitude of hermit life, settling in remote places such as the deserts of Egypt, following the example of Antony the Great, or the mountains of Syria. Byzantine ascetics were often venerated for their piety and wisdom, considered powerful intercessors with God. Eremitism remained a prominent form of Byzantine monasticism until the 15th century. However, female hermits disappeared after the 11th century. In later periods, hermits were generally found on holy mountains like Mount Olympos, Auxentios, Athos, Ganos, and Meteora.

Among these hermits, some practiced particularly rigorous asceticism, such as stylite saints and recluses (enkleistoi). Eremitism was generally regarded in Byzantium as superior to cenobitic monasticism due to the greater hardships of solitary life and the opportunity for spiritual improvement. Usually, a monk had to spend three years in a koinobion (a community of monks) before receiving permission from the hegoumenos (the superior) to become a hermit. Many monks moved back and forth between cenobitic and eremitic life. Tensions sometimes emerged between the two ways of life. Thinkers like Basil the Great and Eustathios of Thessalonike criticized the excessive self-concern, lack of charitable practice, and the impossibility of material self-sufficiency in eremitism.

Next to the hermits, the “holy fools” were individuals who adopted strange, even scandalous behavior, in order to renounce their own will and submit entirely to God. They could, for example, walk naked in public, insult the authorities, or feign mental illness. The “holy fools” were often misunderstood and persecuted, but some have been venerated as saints after their death.

Although these different types of ascetics were on the fringes of the Byzantine clergy, they had a profound influence on the religious life of the Empire. However, during the middle and late Byzantine periods, most of these movements were integrated, in one form or another, into regular monasticism.

Sources:

- “Byzantium: The Eastern Roman Empire” by Michel Kaplan

- “Eastern Christianity” by Jean-Marie Gueullette

- “The Monks and the Mountain: The Hermits of Mount Athos” by Jean-Yves Leloup