Byzantine Culture

Byzantine culture is rooted in the continuation of the traditions and knowledge of classical antiquity, adapted to Christianity and blended with various oriental influences. The Byzantines saw themselves as the direct heirs of the greatness of Rome and of Greco-Roman culture. Education was deeply steeped in this heritage, and the Byzantines were careful to preserve and perpetuate it. However, during the eleven centuries of the Empire’s existence, the Byzantines also developed a distinct artistic tradition, while the elements of their culture – language, cuisine, music – evolved slowly. After the fall of the empire, the Byzantine cultural legacy endured and many of its aspects were adopted by Ottoman society.

Byzantine languages : Latin, Greek koinè and vulgar greek.

The shift from Latin to Greek.

During the Hellenistic period (-323 to -30) and following the Macedonian conquest, huge territories fell under Greek dominance. To allow communication within vast empires, whose population had their own native languages, a common Greek known as koinè (meaning “common”) emerged, independent from the ancient Greek dialects like Doric, Aeolic, Ionic, or Attic. This language was used by the administration and allowed communication between the different people composing the Hellenistic states and the Roman Empire. Therefore, the Eastern Roman Empire had always used Greek not only as a common language but also for administrative purposes. The Western part used Latin, even though the Roman elites were also largely Hellenized. However, the foundation of Constantinople and the shift of the capital was intended as a sort of translatio of Rome itself. Roman families moved, bringing Latin as their own language. The administration set up in Constantinople also used Latin first, and so did the emperors, even though they could also command Greek. However, as most of the local people of the empire were speaking Greek, a progressive shift occurred.

The last Roman Emperor to predominantly speak Latin was likely Justinian I (527 to 565 AD), and if his successors could still command Latin, they used Greek as their main communication language. The transition from Latin to Greek as the primary language of administration occurred gradually over several centuries. While Latin remained in official use during the early Byzantine period and until the reign of Heraclius (610-641), Greek gradually gained prominence due to its widespread use among the population and its cultural significance. By the 7th century, Greek had become the predominant language of administration, and Latin was largely abandoned. This linguistic shift was largely complete by the 9th century AD, although Latin could still occasionally be used on coins.

However, Latin didn’t completely disappear. Even in the Byzantine Empire, some regions were still predominantly populated by Latin-speaking people. Romania was a good example, but it is also true for the numerous “Valaques” or “Vlaques” relics in the Balkans. The Byzantines also retained some knowledge and use of Latin for several hundred years after abandoning it officially, event if it was essentially considered a foreign language. Nonetheless, remnants of Latin remained within the technical vocabulary, especially in the military and in the law.

The Byzantine koinè and the vernaculer Greek.

The koinè had standardized grammar, was taught in schools, transmitted by writers, adopted by administrations and merchants, and facilitated Greek becoming the common language for a considerable number of foreigners (Syrians, Egyptians, Arabs, Jews, etc.), serving as a unifying element, much like Latin in the Eastern part of the empire or English today. However, the pronunciation of koinè speakers could vary considerably depending on their native language or dialect. The language evolved: different sounds, iotacism, confusion of cases (Greek is inflected), abandonment of certain tenses like the optative, future, or indicative. A vernacular language, with a popular character, emerged alongside the written language, which retained its original spelling and grammar. This process had already begun before the Byzantine era and continued thereafter.

Nonetheless, Byzantine scholars used the koinè. Some writers, though few, even chose to use the Attic dialect, such as Anna Comnena. Thus, the literary language of Byzantium was not the language of everyday conversation. It was an artificial language, not understood by the common people and not used by scholars themselves in everyday life. However, this vernacular language did influence the production of Byzantine scholars. Foreign words, Latin, Arabic, or Armenian, for example, were gradually introduced by authors from the 6th century onwards, and certain grammatical rules were no longer observed. Nevertheless, for over a thousand years, the ancient language remained the literary language. Conversely, the vernacular language was looked down upon by scholars and educated individuals. In the 12th century, Patriarch Nicholas Muzalon had a life of a saint written in vulgar Greek burned. This vernacular language did not even have a name in the Byzantine sphere. It was the Westerners who called it Romaic, from which the modern Greek language derives today.

In the mid-11th century, a true reform of Byzantine koinè occurred. The greatest intellectual of the time, and perhaps of Byzantine history, Michael Psellos (1018-1078), was its promoter. He recommended the use of koinè, its vocabulary, and ancient forms, and placed great importance on spelling in his teaching. His own written language largely followed the classical tradition but showed partial disorganization of declensions and conjugations. He admitted both Attic and later forms for nouns and adjectives. He eliminated some augmentations and mixed conjugations. Finally, the influence of the vernacular language was sometimes evident in his writings. He certainly influenced Princess Anna Comnena, who chose Attic rather than koinè out of linguistic purism for her Alexiad. However, she also fell into similar inaccuracies.

The capture of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 struck at the heart of Byzantine civilization and constituted a rupture both politically and culturally. The first works written in the vernacular language began to appear, such as the Chronicle of Morea and the poems of Constantine Metchites in the 14th century. Nevertheless, even he affirmed the primacy of koinè and wrote: “By race and language, are we not the compatriots and heirs of the ancient Hellenes?”

Admiration for the ancient language was even stronger among the promoters of the Hellenic Renaissance in the 15th century, who nevertheless used the vernacular language in their private correspondence.

Christianity and Antiquity: Merging classical heritage with the new faith in Byzantium.

The Byzantine Empire was unique in its ability to blend the legacy of classical antiquity with the Christian faith, creating a distinctive cultural, intellectual, and artistic tradition. This synthesis was achieved over centuries, as the empire inherited the Greco-Roman traditions of the Eastern Roman Empire while adopting Christianity as its official religion. The result was a civilization that both preserved the achievements of antiquity and transformed them to reflect its spiritual ideals.

Philosophy and Education.

Byzantine education and intellectual life were deeply rooted in classical traditions. The curriculum in schools revolved around the study of classical Greek and Latin texts, including works by Homer, Plato, and Aristotle. However, these texts were reinterpreted through a Christian lens. For instance, Neoplatonism, which emphasized the metaphysical and the divine, was harmonized with Christian theology to explore concepts like the nature of God, creation, and the soul. Prominent Byzantine thinkers such as John Damascene and the Cappadocian Fathers used classical philosophical tools to articulate and defend Christian doctrines, ensuring that classical heritage remained central to Byzantine intellectual life.

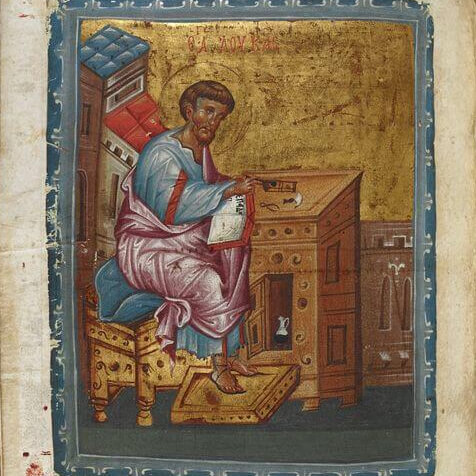

Art and Architecture.

In art and architecture, the Byzantines merged classical forms with Christian symbolism, creating a unique aesthetic that evolved over time. Early Christian basilicas, such as the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, borrowed architectural elements from Roman public buildings, including columns, arches, and domes. The crowning achievement of Byzantine architecture, Hagia Sophia, exemplifies this synthesis. Its massive dome, a feat of Roman engineering, was imbued with Christian meaning, symbolizing the heavens and the divine. Similarly, Byzantine mosaics, while influenced by the naturalism of classical art, shifted toward a more spiritual, abstract style to convey the transcendence of Christian themes.

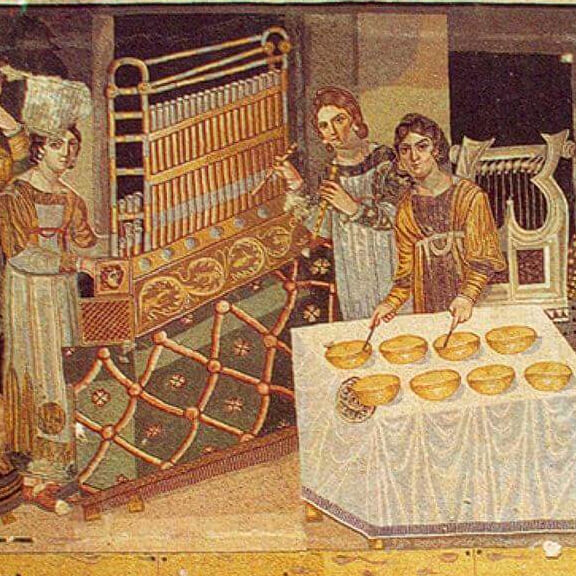

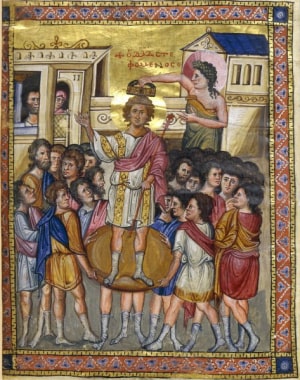

During the Macedonian Renaissance (9th–11th centuries), there was a revival of classical forms and motifs in art and architecture. This period saw a renewed interest in the heritage of antiquity, as artists and architects incorporated classical proportions, naturalistic details, and complex compositions into their work. Iconography became more refined, with figures depicted in fluid poses and with greater attention to detail. In architecture, the cross-in-square church plan emerged as a dominant style, reflecting both functional and symbolic innovations. Monasteries such as Hosios Loukas in Greece demonstrate this blend of classical inspiration and Christian devotion.

The Palaiologan Renaissance (13th–15th centuries) marked another flourishing of Byzantine art and architecture, characterized by intricate decoration, heightened emotional expression, and regional diversity. This era followed the empire’s recovery of Constantinople in 1261, sparking a cultural revival. Art from this period, including frescoes and mosaics, exhibited a richer color palette and more dynamic compositions, emphasizing spiritual transcendence and human emotion. Notable examples include the mosaics of the Chora Church in Constantinople, which showcase a masterful blend of classical elegance and Christian storytelling. In architecture, there was a renewed focus on smaller, intricately designed churches, often adorned with elaborate brickwork and carved details.

Both renaissances reflect Byzantium’s enduring engagement with its classical past, continually reinterpreted to express the spiritual and cultural ideals of its time. This ability to draw from antiquity while embracing innovation ensured the vitality of Byzantine art and architecture across centuries.

Sculpture and statues.

The Byzantine attitude toward sculpture and statuary reflects a significant departure from classical traditions and often reveals an ambiguous stance. While the Greco-Roman world celebrated monumental free-standing statues, typically depicting gods, heroes, or emperors, Byzantium largely abandoned this practice— even for imperial propaganda—after the 6th century, primarily due to its association with pagan idolatry. Instead, the focus shifted to bas-relief sculpture, which adorned churches, altars, and sarcophagi with Christian themes. Relief carvings frequently depicted biblical scenes, saints, or symbolic motifs like the cross or the lamb, blending classical techniques with Christian iconography.

However, the use of classical statues was not entirely abandoned. In some cases, pagan statues were repurposed for decorative or symbolic purposes, such as in public spaces or imperial contexts. For example, statues of ancient gods or emperors might be displayed in Constantinople to evoke the grandeur of antiquity while serving a neutral or Christianized function. Some classical sculptures were preserved as valuable artifacts, admired for their craftsmanship but stripped of their original religious significance. This careful negotiation between rejection and preservation highlights how Byzantium redefined sculpture to align with its spiritual and cultural priorities while maintaining an often ambiguous attitude toward its classical heritage.

Literature and rhetoric.

Byzantine literature often drew on classical genres such as epic poetry, historiography, and rhetoric, but these forms were adapted to serve Christian purposes. Writers like Procopius continued the tradition of classical historiography, while saints’ lives (hagiographies) became a popular genre, blending classical narrative styles with Christian moral teachings. The use of rhetorical techniques, a hallmark of classical education, was evident in the sermons of church fathers like John Chrysostom, who used persuasive speech to communicate Christian teachings.

Legal and political systems.

The Byzantine legal system, epitomized by the Code of Justinian, preserved Roman legal principles while integrating Christian values. Laws were adapted to reflect Christian morality, addressing issues such as marriage, family life, and the treatment of the poor. Justinian’s codification not only systematized Roman law but also established a legal framework that heavily influenced both Byzantine governance and later medieval European legal traditions.

Canon law, the body of ecclesiastical regulations governing the Church, played a crucial role in Byzantine society. It was closely intertwined with civil law, reflecting the empire’s theocratic nature. Canon law addressed matters such as clerical conduct, church administration, and the sacraments, while also influencing secular issues like inheritance, marriage, and moral behavior. The symphonia, or harmony, between Church and State was a guiding principle in Byzantine governance, with emperors often convening church councils to resolve doctrinal disputes and codify ecclesiastical laws.

Politically, Byzantine emperors adopted the Roman model of centralized authority but infused their rule with Christian ideology. The emperor was regarded as God’s representative on earth, tasked with protecting the faith and upholding divine order. This fusion of imperial and ecclesiastical authority ensured that both civil and canon law worked in tandem to govern the empire, maintaining a balance between spiritual and temporal power.

This integration of Roman legal tradition, Christian ethics, and canon law exemplifies how the Byzantines redefined governance to align with their spiritual and cultural priorities, leaving a lasting legacy in both the Eastern and Western worlds.

Religious practices and Classical Culture.

The Byzantines found ways to Christianize classical cultural practices, often replacing pagan festivals with Christian holidays and converting temples into churches. Icons and relics became central to Byzantine worship, reflecting a shift from the Greco-Roman emphasis on monumental sculpture to smaller, more personal objects of devotion. Yet, even as the empire adopted Christianity, it continued to admire and preserve classical art and artifacts, recognizing their cultural and aesthetic value.

Interestingly, some pagan festivals persisted well into the Byzantine period, albeit in modified forms. For example, ancient agricultural and seasonal celebrations were sometimes integrated into Christian practices or observed unofficially by rural communities. This blending of traditions underscores the complexities of the empire’s cultural transformation, where pre-Christian customs coexisted alongside established Christian rituals, particularly in outlying regions.

This ability to reinterpret and adapt classical traditions to fit Christian ideology exemplifies the Byzantine approach to its cultural heritage, creating a civilization that honored its past while advancing its spiritual and cultural ideals.

The Time in the Byzantine culture: Calendar and feasts.

In this domain, as in many others, Byzantium is the continuation of Rome. The hours of the day, the months, the way of placing the days within the months according to the system of the calends, the ides, and the nones, remains the same during the first Byzantine centuries as it was during antiquity. But from the 4th century, the Christianization of the empire calls into question the measurement of time as a political and ideological issue. Can the reference point for counting the years remain the foundation of Rome, in an empire now dominated by an eschatological religion, which awaits the end of the world and inherits a history of its origins revealed? Furthermore, the Christian religion quickly proves to be intrusive, and its liturgy claims to rhythm the life of a part of the inhabitants of the Empire, the clergy first, then the monks. The passage of time during the year is also a public concern, as the imperial power lives in part from the taxes it levies annually, at a fixed date.

The three levels of the calendar for the Byzantines : days, months and year.

The calendar has three levels: the days within the months, as defined by the Julian calendar dating back to Julius Caesar, the months of the year, and the counting of the years that succeed each other. For the days, the novelty is total, as the week is now offset from the solar months of the Julian calendar. For it is the account of Genesis that imposes itself: God created the world in six days and rested on the seventh. Byzantium adopts the week in all its rigor: it begins with the Day of the Lord (Kyriakè, our Sunday), where God created the earth and the universe, and ends at our Saturday, called “Sabbath.” The Eastern Christians do not retain the names of the other days of the week as they came from Egypt, and as we know them today in reference to the planets. Monday is simply the “second” day (after Sunday), Tuesday the “third,” Wednesday the “fourth,” Thursday the “fifth,” while Friday becomes the day of “preparation” (Paraskévè) for the Sabbath. However, official acts, chroniclers, and even ecclesiastical writers generally do not use the days of the week but simply the quantième of the month.

For the months of the year, Roman usage imposes itself, which conserves for the most part the reference to a pagan god (January for Janus, Mars, June for Juno) or a pagan personality (July for Julius Caesar, August for Augustus). The Roman year began in March, but the beginning of the year had been moved as early as the 3rd century to September 1st, and the Byzantine Empire retained this usage until its fall. The East, moreover, does not know the interminable debates that the West knows to fix the date of Easter.

Concerning the year, dating from the foundation of Rome became excluded. Dating by the reign of the emperors could only come in second place, as they changed frequently, and the beginning of their reign never coincided with the beginning of the year. Dating according to the consuls who succeeded each other each year, also a Roman usage, did not survive the disappearance of the consulate in the 6th century. Little by little, the dating from the creation of the world imposes itself, in the perspective of the return of Christ on earth, which will mark the end of the world and the Last Judgment. But the calculation of the creation of the world, based on the accounts of the Old Testament and the genealogy of Christ in the Gospel of Matthew, can give different results. In the 7th century, the Byzantine era imposes itself. It results from an alignment that dates the creation of the world to March 31, 5008 BC. Henceforth, all official documents date in the year of the world from September 1, 5509. At that time, it was believed that the world lived in cycles of a thousand years, that Christ was born in the middle of the sixth cycle, and that there would probably not be a seventh. However, there does not seem to have been any anxiety around the approach of the end of the cycle, which should have been around the year 500. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Patriarch Gennadios Scholarios, under Ottoman domination, could think that the end of the world would take place at the end of the seventh cycle, around 1492. This belief had moreover spread during the last century of existence of the Byzantine Empire, whose subjects themselves anticipated the fall.

The administrative character of this way of dating is reflected in another institution: the indiction, which is initially of a fiscal nature. It dates back to the reform of Diocletian, accompanied by a cadastral survey of the lands and the means of exploiting them, in 297. Henceforth, the indiction is the cycle of 15 years that separates two revisions of the cadastre. However, the number of indictions since 297 is quickly forgotten, and the years are simply noted according to their rank in the indictional cycle. Therefore, all the years are between one and fifteen. This type of dating, which is frequent in the sources and probably in daily life, defines the date only to a multiple of fifteen – for example, November, indiction 3. It is then necessary to refer to other contextual elements to deduce the precise year.

The feasts, a mixture of pagan legacy and christianity.

If the Byzantines’ awareness of the passage of the seasons is not original, the high points that mark the unfolding of the year signal another contact between the Roman and pagan world and a civilization that claims to be Christian. Certain pagan feasts thus persist more or less for a long time. The Lupercalia, festivities celebrating the foundation of Rome and fertility, were maintained only until the 6th century. But the feast of the vows (Bota, January 3rd) still gave rise to sacrifices in the 7th century and the organization of races at the Hippodrome in the 10th century. The Brumalia, feasts of Dionysus, celebrated from November 24th to December 21st, marking the end of the fermentation, still existed in the 6th century. Despite the excommunication decided by the Council in Trullo in 692, they were still practiced at the imperial court in the 10th century and had not yet disappeared in the 12th.

To this are added civic feasts. In Constantinople, the main one was March 11th, the anniversary of the inauguration of the capital by Constantine. It was the occasion for the most splendid chariot races of the year at the Hippodrome, accompanied by distributions of bread and fish. In the provincial cities, the civic feast corresponded rather with the religious feast of the patron saint, whose relics the city possibly possessed.

For the countryside, the rhythm is more closely calqued on the seasons and the corresponding work. Our knowledge of it is very fragmentary, but it seems that two feasts corresponded quite well to the solstices – the Nativity in winter and Saint John the Baptist in summer. Christianity would thus have rather assumed the pagan customs rather than confronting them.

But the empire being Christian, the calendar of liturgical feasts, which are very numerous, superimposes itself. In addition to the main feast, Easter, the cycle of the twelve (other) feasts includes three movable feasts related to Easter: Palm Sunday, the Ascension, and Pentecost; and nine fixed feasts: the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Epiphany, the Purification of the Virgin or Hypapante, the Transfiguration related to Christ, and the Birth, Presentation, and Dormition related to the Virgin, to which is added the Exaltation of the Cross. To these feasts are added the feast of the Circumcision, two others related to Saint John the Baptist (his birth and his beheading) as well as the feast of Peter and Paul. This collection of major feasts can be found assorted with local feasts. Indeed, each city and village had its patron saint, whose feast is part of the identity of the community. Thus, in Thessaloniki, the patron saint of the city, Demetrios, has been celebrated since the 5th century on October 26th, giving rise to one of the most important fairs of the empire.

Byzantine Education : Transmitting the culture.

Educating children, especially among the upper class of society, was of utmost importance, as many career paths in the Church or administration depended on it. Byzantium inherited the paideia of antiquity, preserved it, and occasionally perfected it.

The elementary education: Propaideia

The crisis of the cities in the 5th and 6th centuries led to the disappearance of municipal schools. But the primary school, entrusted to a grammatist, responsible for teaching letters (grammata) remained widely widespread even in small towns in the depths of Asia Minor. This is the propaideia, a preparation for future paideia. The letters and grammar are taught most often in sacred texts, which also provides the basics of a religious education, but also in Homer. Women can also benefit from it: the 9th century saint Theodora of Thessaloniki, native of the island of Egine, from a good family, learned in a psalter. The future empress Theophano, first wife of Leo V, in the hymns.

This first education begins at 6 or 7 years old and lasts 4 or 5 years. The masters are humble characters: there is no example of a subsequent career in paideia. The schools are private and tuition-based, but the cost as well as the content remain relatively affordable. A number impossible to estimate but not negligible of Byzantines know how to read and even write. These qualifications were indispensable for certain professions, even humble ones, such as the priesthood or trade.

The secondary education: Paideia and the Constantinople school system

At the age of 10 or 11, the child begins paideia. At this stage, no female school is known. The secondary school never disappeared, but the sources do not allow us to understand it again until around the 9th century. At that time, it was entirely centered on Constantinople. The future apostles of the Slavs, Constantine-Cyril and Methodius, of a good Thessalonian family, could not do their paideia in their city (although the second most important in the empire) and had to leave for the capital. The school of Constantinople is quite well known thanks to the correspondence of a 10th century teacher who remained anonymous. He is a bachelor, lost in his books, hardworking, who must support his entire family displaced from Thrace because of the Bulgarian invasions. This book lover who sells, buys, exchanges, receives or gives them, is a teacher and director of a didaskaleion (or paideutèrion), where he dispenses to his students the general education (englyklios paideia). Each school has, in principle, only one master (maistôr) assisted possibly by an assistant (proximos). A school welcomes children of all ages and all levels, who stay there for at least 6 or 7 years. The students are therefore relatively numerous and of different levels. The most advanced are the ekkritoi or epistates. The teacher teaches mainly to the ekkritoi and they to the little ones; the teacher controls the process once or twice a week. The anonymous teacher complains about his students. Very free, they mock his remarks and willingly play hooky; they have a consumer attitude, even clients, and their social condition is visibly better than that of the teacher.

Teaching is a profession that is poorly paid and not well-regarded, which the sons of the aristocracy disdain. They form, however, the majority of the clientele, even if at certain periods, certain social circles, notably merchants, have also seen in the education of their children a means of social progress. The teaching is entirely (or almost) private and tuition-based. This results in a struggle to access the teaching profession in the best schools: the revenues depend above all on the number of students. The anonymous teacher complains about his difficulties both with the parents, for his salary, often late and left to their appreciation, and with his colleagues: the competition is severe and not always loyal. The students often change schools, looking for the best-rated teacher. In the 10th century, the emperor tried to bring order by creating a president of the schools and appointing for part the masters. Later, the patriarchate became involved in the teaching, without it ceasing to be above all of secular content, even if most of the schools are located in buildings annexed to ecclesiastical establishments. Note in favor of the quality of this teaching that the greatest intellectuals, such as Leon the Mathematician in the 9th century or Michael Psellos in the 11th century, practiced the profession of maistôr. The most famous school, that of Saint-Peter, where Psellos exercised, had several masters and taught a wide spectrum of disciplines. The school knew a new boom under the Palaiologoi in the 14th and 15th centuries, a time when culture became a concern of the entire aristocracy.

The heart of the school program is the trivium: grammar, poetry, rhetoric. The fundamental method is learning by heart: it is about acquiring the language, the forms, the qualities of expression drawn from the distant past of Hellenism. The students engage in composition exercises based on the imitation of models and the banishment of all personal accent – the opposite of the values of creativity sought today. In the 11th century, this gave rise to the schédographie, an exercise that consists of concentrating a maximum of lexicographical, stylistic and grammatical difficulties in a minimum of words. The result is of great obscurity. The schools engage in competitions between students, where the teachers cheat without shame, given the stake that it represents for them. The goal is therefore to perfect the beautiful language, the one that the child acquires naturally from his parents when they already practice it. The teaching reproduces the model provided by the dominant class, the aristocracy of function. It serves above all to train the officials of the civil and ecclesiastical administration. It is theoretically open to whoever can pay and, in the 11th century as at the end of the Empire, the merchant bourgeoisie sends its children there. But money does not necessarily guarantee success and the teaching is characterized by a very strong class character.

The University and higher education.

As for the University, it disappeared after Justinian and was not reborn until the second half of the 9th century, nearly two centuries before its Western equivalents. It was the imperial power that initiated this renewal. It was entrusted to Leon the Mathematician with a public objective: “to remedy the rusticity and ignorance of the rulers”. This university lasted at least until Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (913-959), with at least four chairs: grammar, arithmetic, geometry and philosophy. In the 11th century, Constantine Monomachus created a higher school of Law, also to train officials. We must then wait for the time of the Palaiologoi to see the rebirth of a true higher education.

For the other domains of the Byzantine Culture, have a look to the categories below!

Byzantine Religion

The Christian Orthodox faith served as a cornerstone of Byzantine society.

Byzantine Society

Inheriting the hellenic legacy, the Byzantines cultivated a unique and distinctive culture of their own.

Byzantine Science

Who were the Byzantines? Uncover the women and men behind the history.