Byzantine mosaics : Masterpieces of color and design

Among the artistic achievements of Byzantium, mosaics stand as the most enduring and distinctive. More than decoration, they embody a vision of divine beauty expressed through light, color, and geometry. The Byzantine mosaic is often associated with the use of gold – an element that later inspired Klimt in the 19th century – creating a shifting brilliance seen as a metaphor for divine revelation. It enhanced the experience of the sacred, shimmering in the glow of gold and glass, in holy spaces such as churches and imperial palaces.

Challenge of Byzantine mosaics creation and rendering.

Unlike fresco, which involves painting on wet plaster, mosaic is an additive medium. Artists place small pieces of material, the tesserae, one by one to create an image. Each tessera reflects light differently, producing an effect that changes with the viewer’s movement.

late 13th century icon of the Virgin Eleousa type, Byzantine Museum of Athens.

This technique emphasizes line and contour, which can be difficult to balance. However, mosaics were often designed to be viewed from afar. The faithful, standing on the ground of the church, would raise their heads to see the mosaics on the dome or upper levels. Seen from a distance, under soft light or candlelight, the tesserae themselves became less visible, and the overall image appeared harmonious.

For works meant to be viewed closely, such as miniature icons from the 11th century onward, artists used microscopic cubes to soften the visual effect. The results show remarkable skill and precision.

Creating a mosaic required both artistic vision, technical mastery, and financial effort. Artists followed painted sketches, embedding tesserae into fresh plaster in carefully planned sections. Materials varied: stone, brick, and terracotta for structure; colored glass, marble, and semiprecious stones for brilliance. Large-scale projects demanded vast resources, often only available for the imperial family, the upper aristocracy or the wealthiest religious institutions. The apse of Hagia Sophia alone contained nearly 2.5 million tesserae, many coated in gold. Even if a skilled craftsman could cover several square meters per day, depending on tessera size, mosaics were extremely costly compared to the cheaper fresco technique.

Despite these limitations, mosaics could achieve great subtlety and complexity. Artists used hundreds of color shades to create intricate, lifelike images. During prosperous times, expensive mosaic programs flourished; in later centuries, mosaics were reserved for the most prestigious commissions.

Origins and early development.

The mosaic tradition of Byzantium emerged from the artistic languages of Greece and, especially, Rome. During Roman times, mosaics flourished as decorative flooring. Early Christian communities adapted Roman floor mosaics for new sacred spaces. From the 4th century onward, as Christianity gained imperial recognition, mosaics moved from the ground to the walls and ceilings of churches.

This transformation marked a profound change in meaning. Depictions of Christ, the Virgin, and the saints were lifted above the faithful, no longer beneath their feet. Church interiors evolved into cosmic visions—reflections of heaven on earth—with decorative programs growing more elaborate over the centuries.

Floor Mosaics: From figures to geometry.

Floor mosaics were the earliest form of Byzantine mosaic art. In direct continuity with Roman traditions, they decorated villas, baths, and later, church floors. Their designs combined geometric patterns, vegetal motifs, and symbolic imagery. Durable materials—such as marble and colored stone—made them ideal for public and domestic use.

In Christian contexts, floor mosaics carried symbolic and didactic purposes. Fish, vines, and crosses hinted at theological ideas without direct figural imagery. Over time, as sacred imagery was considered inappropriate for walking surfaces, floor mosaics became more abstract and ornamental.

Until the 6th century, floor mosaics were widespread across the Byzantine Empire, as shown by examples from Madaba, the Balkans, and the Great Palace in Constantinople. From the reign of Emperor Justinian I onward, floors were increasingly paved with marble, while walls, domes, and ceilings became the main stages for mosaic art.

Yet, the craftsmanship and compositional logic of floor mosaics continued to influence later Byzantine design.

In the Middle and Late Byzantine periods, floor mosaics featured fewer figures and often took the form of opus sectile – a technique where pieces of colored stone, marble, or glass are cut into specific shapes and fitted together to form pictures or geometric patterns.

Wall and ceiling mosaics: Sacred visions in glass and gold.

Late Roman and early Byzantine artists had already achieved great skill in wall mosaics by the 4th and 5th centuries, as seen in Rome and Ravenna, for example in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia.

The reign of Justinian I marked a zenith with the construction of Hagia Sophia, which set a new standard with marble-clad floors and walls rising to glittering vaults of gold mosaic. This combination of materials created a visual hierarchy: earthly solidity below, celestial radiance above.

Wall mosaics spread across the empire, decorating official and sacred spaces during Justinian’s extensive building campaigns. The mosaics of Ravenna, Thessaloniki, Sinai, and Hagia Sophia remain the best surviving examples.

The technique became more sophisticated. Artists used thousands of color shades for subtle modeling and expression. Gold and silver tesserae, made by placing metallic foil beneath translucent glass, gave sacred figures an ethereal glow. Small tesserae, sometimes microscopic, refined faces and drapery folds.

The expansion and influence of Byzantine Mosaics in the Middle Byzantine era.

Byzantine mosaicists were in high demand beyond the empire’s borders. Mosaic art became a major Byzantine export, with Arabs importing mosaic cubes and craftsmen for the decoration of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus in the early 8th century. Pope John VII also employed Byzantine mosaicists for his oratory in St. Peter’s in Rome.

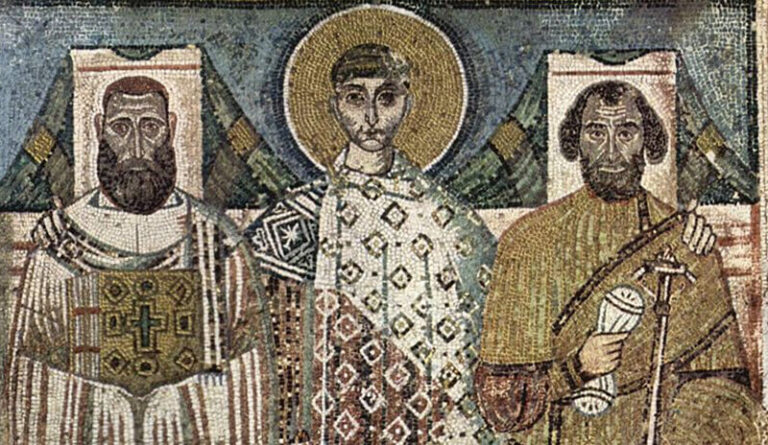

By the late 8th century, mosaics of holy figures became common in sacred decoration. From the Middle Byzantine period, notable surviving examples include the mosaics of Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki, dating from the 7th and 8th centuries. However, the Iconoclast period marked a rupture. Many mosaics were destroyed, and emperors banned figurative decoration, as seen in Hagia Irene in Constantinople, the only surviving example of an iconoclastic mosaic program.

Detail of the mosaics of the Norman Palace in Palermo, image: Holger Uwe Schmitt, CC by SA 4.3

With the Triumph of Orthodoxy and the economic revival of the 9th and 10th centuries, mosaics returned to churches and private chapels in Constantinople. Mosaics also adorned palaces, such as the Kainourgion at the Great Palace built by Basil I.

They illustrated imperial portraits in Hagia Sophia, like the Zoe mosaic or the Komnenos mosaic, from the 9th to the 11th century and historical scenes under Emperor Manuel I (1143-1180). None of the secular mural mosaics survive, though the Ruggero Room in the Norman Palace in Palermo gives an idea of their lavish style.

In emulation of Empress Helena, Manuel I may have sent mosaic cubes and craftsmen, such as Ephraim, to Bethlehem for the Church of the Nativity. Clavijo describes mosaics in the church and cloister of the Peribleptos Monastery in Constantinople, as well as in St. George of Mangana, dating to the 12th or 13th century. Large areas of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople were decorated with mosaics by Eulalios in the 12th century.

The 11th and 12th centuries marked a high point for mosaic art, with artists and materials transported across long distances for projects such as Hosios Loukas, Nea Moni on Chios, and Daphni, near Athens. In the early 11th century, mosaicists were sent to Kiev to embellish St. Sophia and teach local craftsmen. A similar exchange likely occurred during the decoration of San Marco in Venice, and Byzantine mosaicists worked for Desiderius of Montecassino. The Norman kings of Sicily also commissioned mosaics partly crafted by Byzantine teams or inspired by Byzantine models.

Decline and Legacy in the Late Byzantine time.

After the fall of Constantinople to the Crusaders in 1204, economic and political challenges reduced mosaic production, which remained far costlier than fresco. Mosaics became limited to the wealthiest or most prestigious locations: Constantinople, Thessaloniki, and parts of the Despotate of Epirus. In Constantinople, panels in Hagia Sophia, including those restored after an earthquake in the 14th century, continued the tradition. In the Despotate of Epirus, the churches of Panagia Paregoritissa and Panagia Porta received elaborate wall mosaics, while the Panagia Vlacherna preserved a fine floor mosaic.

The final flowering of Byzantine mosaic art occurred in the 14th century, when restoration work in Hagia Sophia revived its golden surfaces once more. Later churches, including Chora and Pammakaristos, combined mosaics with frescoes, reflecting both continuity and adaptation.

Enduring brilliance and legacy of the Byzantine mosaics.

Byzantine mosaics remain one of humanity’s greatest artistic achievements and the emblem of Byzantine artistic legacy, recognized by numerous inscriptions in the UNESCO World Heritage List. Their luminous surfaces, technical mastery, and profound symbolism transformed architecture into a vision of paradise. Whether adorning church domes or palace halls, they captured the spiritual heart of Byzantium – a world of light, order, and divine beauty. Long after the fall of Constantinople, the legacy of Byzantine mosaics endured in Orthodox, Islamic, and Western art, spreading worldwide through the Neo-Byzantine style.

Explore the world of Byzantine mosaics.

-

The mosaic of Zoe Porphyrogenita and her husbands with Christ in Hagia Sophia

Discover the mosaic of Zoe Porphyrogenita and her husbands with Christ in Hagia Sophia, a testament to the end of the Macedonian dynasty.

-

The Mosaics of the Church of the Panagia Paregoritissa in Arta

Explore the Byzantine mosaics of Panagia Paregoritissa in Arta: a grand yet unfinished artistic legacy of the Despotate of Epirus.

-

Architecture | Art | Church | Mosaics

Byzantine Iconoclast Art and Mosaics at Hagia Irene, Constantinople – Istanbul

Discover the mosaics and decoration of Hagia Irene, one of the oldest Byzantine churches of Constantinople, and a rare witness to early Byzantine art.

-

Discovery of a 1,500-year-old Byzantine monastery in Southern Israel

Archaeologists uncover an early Byzantine era monastery in Israel, revealing stunning mosaics, a winepress, and pottery workshop.

-

Mosaic unearthed in the excavations of a byzantine monastery in Turkey

Archaeologists have unearthed a mosaic dating to the 5th or 6th century in the ruins of a monastery dedicated to Saints Constantine and Helena near Fatsa, Turkey.

-

The Komnenos mosaic in Hagia Sophia : John II, Irene, Alexios, the Theotokos and Child

The Komnenos mosaic in Hagia Sophia is the only 12th-c. mosaic surviving in Istanbul, and shows prominent members of the dynasty with the Theotokos.

-

The mosaics of the church of Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki

Discover the mosaics of the church of Saint Demetrios in Thessaloniki. Dating back to the 6th and 7th c, they were nearly destroyed in 1917.

-

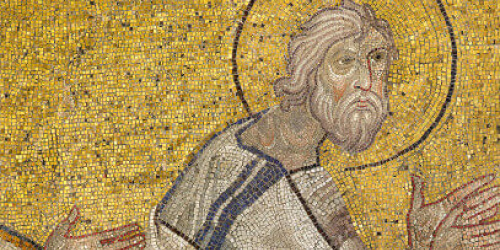

The panel of apostle Andrew, sole survivor of the mosaics of the Serres cathedral

Sole survivor of the mosaics of a greek church destroyed in 1913, this late 11th or early 12th c. panel depicts the apostle Andrew.