Byzantine Religion

To fully grasp the richness of Byzantine heritage, one must first understand its religion, the force behind much of its art and architecture. Christianity, intertwined with Roman identity, shaped the very fabric of Byzantine society, replacing centuries of pagan traditions and defining cultural, political, and spiritual life. From the evolution of early Christian beliefs to the establishment of Orthodox practices, religion guided the empire’s laws, education, and artistic expression. Exploring this progression offers insight into how faith not only structured Byzantine society but also left a legacy that continues in modern Orthodoxy. To trace this transformation, we must return to the final years of the Roman Empire.

The rise of Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire.

When Constantine founded Constantinople, he was not yet a Christian. He authorized Christianity in 313 but initially built temples to the Roman gods in his new capital, even before the first churches. It was only by the end of the 4th century that Christianity became the empire’s official and sole permitted religion. The emperor then assumed the title of “Emperor of the Romans” and added “faithful in Christ the God,” presenting himself as God’s lieutenant on earth, the foremost Christian, and ultimately the head of the Church.

Christianity quickly imposed itself on the masses of the Roman East, extending beyond the empire’s borders into nearby regions and, in some cases, into distant areas of the Persian Empire. Yet paganism persisted among the educated urban aristocracy and declined only gradually. Justinian delayed the closure of the Academy of Athens until 529, and the temple of Philae in Egypt remained active until the 7th century.

Once Christianity was authorized, its leaders no longer opposed Roman identity. Bishops, often drawn from the aristocracy and educated in the paideia, were well-versed in Neoplatonic philosophy and ancient rhetoric. They became some of the strongest defenders of Roman heritage, successfully reconciling it with Christian thought.

The difficult birth of a unified Christian doctrine.

The division of the church at the time of Constantin.

The message of Christ was meant to be universal; the ultimate aim of Christianity was to encompass the oikoumene (literally, the inhabited world), meaning all of humanity. In practice, however, the reality was more complex. The core of Christian belief itself is intricate, teaching one God in three persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. In the early centuries, a vast corpus of scriptures, including many apocryphal texts, circulated among Christian communities. The new religion also encountered the diversity of the ancient world, where beliefs were often deeply rooted in local traditions and supported by established schools of thought. Adding to this complexity, early Christian communities were divided and often clandestine, with differing practices, interpretations, and sometimes even beliefs.

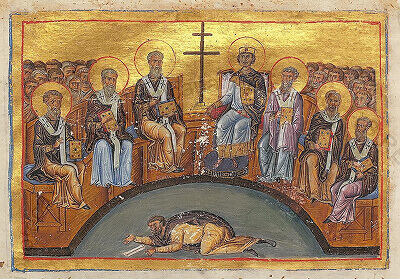

By authorizing Christianity, Constantine made a primarily political choice, regardless of his personal convictions. He sought the support of what appeared to be the most dynamic segment of the empire’s population. Consequently, he could not tolerate Christians tearing one another apart. To address these divisions, he convened the first Council of Nicaea. An ecumenical council normally gathers sufficient bishops and is regarded as speaking for the entire Christian community. Constantine had the council presided over by his representatives. No one contested this role, since he had authorized the new religion. At the time, ideology also considered the emperor as divine in a political sense. While Christians did not see him as God, he was recognized as God’s legitimate representative on earth. This notion remains strong in Orthodox tradition: the emperor, as God’s lieutenant on earth, convenes and presides over councils.

The Arianism dispute and the first concile of Niceae.

The main controversy of the time focused on the relationship between the three persons of the Trinity: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Arius, a priest from Alexandria, advocated strict monotheism, arguing that the Son was a creation of the Father. This doctrine became known as Arianism. It was condemned by the Council of Nicaea, which affirmed that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are of the same substance, a declaration known as the Nicene Creed. However, the issue was far from resolved. Constantine himself recalled Arius from exile as early as 328, and several of his successors embraced Arian beliefs. Arianism continued to spread across many eastern regions and among the Germanic peoples beyond the empire’s borders. The controversy was only settled nearly a century later, at the Second Ecumenical Council of Constantinople convened by Theodosius in 381.

Nestorianism and Monophysism.

Nestorianism and the first Council of Ephesus.

A new controversy arose over Christ’s nature: fully God and fully human. It divided the Eastern Church for centuries. Initially, two main schools of thought opposed each other: those of Antioch in Syria and Alexandria in Egypt. Nestorius, a priest of Antioch who became patriarch of Constantinople in 428, rejected the idea that Christ was born from a woman, arguing that the Virgin was not Theotokos but Christotokos—this became known as Nestorianism. Cyril of Alexandria opposed him, defending Mary’s divine motherhood. The Council of Ephesus in 431 condemned Nestorianism, but the doctrine did not disappear. Nonetheless, Cyril and his school succeeded in promoting a stricter interpretation of Christian dogma, leaning toward a more rigorous monotheism.

The rise of Monophysism.

According to this belief, during the Incarnation, Christ’s human nature merges with his divinity, leaving only one nature (monos physis in Greek). This doctrine is known as Monophysitism. Cyril was able to impose it at a council held in Ephesus in 449. Political considerations soon intervened. When the new emperor Marcian ascended the throne in 450, he sought to avoid alienating Rome, which was less sympathetic to Monophysitism, and to secure the empire’s most threatened regions. He convened a new council at Chalcedon, on the Asian side of the Bosporus facing Constantinople, which condemned Monophysitism in 451.

Despite the council’s decision, Monophysitism remained strong in the eastern provinces, especially in Syria and Egypt. The choice of Chalcedon as the council site suggests that Constantinople’s population might have leaned toward Monophysitism at the time. The crisis ran deep: in the countryside, many resented bishops and tax collectors sent from the capital, and Monophysitism became a vehicle for the revival of local Coptic and Syriac cultures. This religious tension posed a real threat, especially with the Persian Empire as a formidable neighbor to the east, soon replaced by the rapidly expanding Arab forces.

Monophysitism even influenced the Constantinopolitan elite. Justinian’s wife, Empress Theodora, adhered to the doctrine, and several emperors followed her example. Others, particularly in the early 7th century during conflicts with the Persians and Avars, attempted compromises but met little success. Ultimately, the issue was resolved by the loss of the Monophysite regions, which were conquered within about a decade by Muslim Arabs, who would permanently transform the religious landscape of the Near East and North Africa.

The veneration of the images and the iconoclastic crisis.

The veneration of the images.

The divine law given to Moses forbids graven images, the depiction of God’s creatures, and their worship. These commandments are strictly observed by Jewish and Muslim communities, as well as by the most rigorous Christians. As a result, sculptures – including those in the round – are absent in Eastern Christian churches. This contributes to the decline of statuary inherited from antiquity, reducing it to a minor art in Byzantium.

However, there was no unanimous agreement on representations in painting or mosaic. From the earliest days of Christianity, images appeared in churches. They illustrated sacred history for a largely illiterate population, providing indirect access to the Holy Scriptures. According to the Church Fathers of the 4th and 5th centuries, these images were not objects of devotion, unlike imperial portraits, which were honored with lights and incense. At the time, only relics of martyrs—and later of holy men—were objects of veneration.

From the 6th century onward, the situation changed. Portraits of holy men were created during their lifetimes, and images, like relics, were believed to possess miraculous powers. They first circulated privately, then became public and gained significant importance. Some images were even considered acheiropoieta, not made by human hands. Others were carried in procession, such as the image of the Protectress of Constantinople before the city walls during the Avar siege of 626.

Images thus acquired power in themselves, serving as intermediaries between God and humanity, especially as emperors’ credibility declined following military defeats and territorial losses. This belief was reinforced by a long-standing Greco-Roman tradition that attributed divine presence to material objects, predating Christianity.

The first iconoclasm, the councils of Hieria and Nicaea.

Leo the Isaurian, who became emperor in 717, sought to consolidate support during the Arab siege of Constantinople. In the 730s, he began removing images from churches and prohibiting their worship, responding to the concerns of his clergy, especially in Asia Minor. His military successes against the Arabs gave him – and later his son, Constantine V – the authority to enforce this policy at the Council of Hiereia in 754. Iconoclasm then became the official doctrine of the empire.

The controversy focused on whether Christ could be depicted in images, extending to representations of the Virgin Mary and the saints. Theologically, images showing both the divine and human natures of Christ risked implying Monophysitism, while images depicting only his human nature suggested Nestorianism. Under Iconoclasm, only symbolic representations of divinity were permitted: the Cross, the Eucharist, and the Word.

Voices rose in defense of images in response to imperial policy. The main figure of this movement was John of Damascus, a former official under the caliphate who retired to a monastery in Palestine. Being outside the empire, he could write freely. He argued that the Incarnation made God representable: Christ is the icon of the Father. John reversed the iconoclast argument: since Christ is fully human, he can be depicted; denying this risks Monophysitism, which confuses his divine and human natures. If Christ can be represented, so too can the Virgin and the saints. To counter accusations of idolatry, John distinguished between the image—a material object—and what it represents. The image was not worshiped itself but venerated, and the honor given to it passed to what it represented. These two views of the divine proved irreconcilable.

Despite this, the victories of the iconoclast emperors Leo III and Constantine V strengthened their authority. The Byzantine ecclesiastical hierarchy largely submitted to imperial will, which increasingly favored iconoclasm. The only serious opponents were monks who resisted the policy. Many monasteries relied on pilgrims attracted by sacred images and relics. To weaken them, the emperors secularized and dispersed monks from resistant monasteries. Constantine V staged a public mockery at the Hippodrome of Constantinople, parading stripped monks and nuns—men and women paired together—through the track to signify their reintegration into ordinary society. These persecutions were more humiliating than violent. Later iconodule sources portrayed figures like Stephen the Younger as martyrs, but they had actually been punished for conspiracy or lèse-majesté; for instance, Stephen was imprisoned for reconstituting a dissolved monastery and trampling an imperial coin.

-

Architecture | Art | Church | Mosaics

Byzantine Iconoclast Art and Mosaics at Hagia Irene, Constantinople – Istanbul

Discover the mosaics and decoration of Hagia Irene, one of the oldest Byzantine churches of Constantinople, and a rare witness to early Byzantine art.

Iconoclasm never gained universal support. It faced resistance from parts of the population and from the papacy, which turned to the Carolingians, threatening Byzantine holdings in Italy.

To break this isolation, Empress Irene, regent for her son Constantine VI, restored the veneration of images. She convened a council at Nicaea in 787, supported by the pope, though the population of Constantinople remained divided, with many still favoring iconoclasm.

This enduring support would make the second wave of iconoclasm possible under Leo V.

The second iconoclasm and the definitive restoration of images.

The iconodule emperors who followed faced repeated defeats against the Bulgars. In 813, the Bulgars even besieged Constantinople, and the panicked population rushed to the tomb of Constantine V – an iconoclast, but a victorious one. In 815, Leo V reinstated the Council of Hieria, while conceding that the veneration of icons could not be considered idolatry. His two successors continued this policy. The ecclesiastical hierarchy was again purged, and a few monks resisted once more. However, this second period of iconoclasm lacked the vigor and unity of the first.

In 843, Empress Theodora, acting as regent for her son Michael III, restored the veneration of images permanently. This event is still celebrated as a feast in the Orthodox Church.

The crisis left deep and lasting effects on Byzantine life and art. Portable icons became widespread in homes, and their designs were gradually standardized. Church walls were again decorated with frescoes and mosaics, following an established program: Christ Pantocrator appeared in the dome, the Virgin in the apse, and saints’ portraits adorned the walls. At the same time, the pilgrimage of relics experienced a renewed boom, reflecting the resurgence of popular devotion.