Byzantine sculpture: An overlooked art

The history of Byzantine sculpture differs markedly from that of architecture, mosaics, and painting. A key characteristic was the abandonment of sculpture in the round (three-dimensional statues). This technique, associated with “pagan idolatry,” faced strong opposition from theologians and was quickly abandoned. As a result, monumental sculpture in the round did not survive beyond the 6th century, despite its earlier prominence in imperial art. The Byzantines thus faced a paradox: the sculptural legacy of antiquity remained visible, yet statues were treated with suspicion and no longer produced.

Statuary in the Late Antiquity.

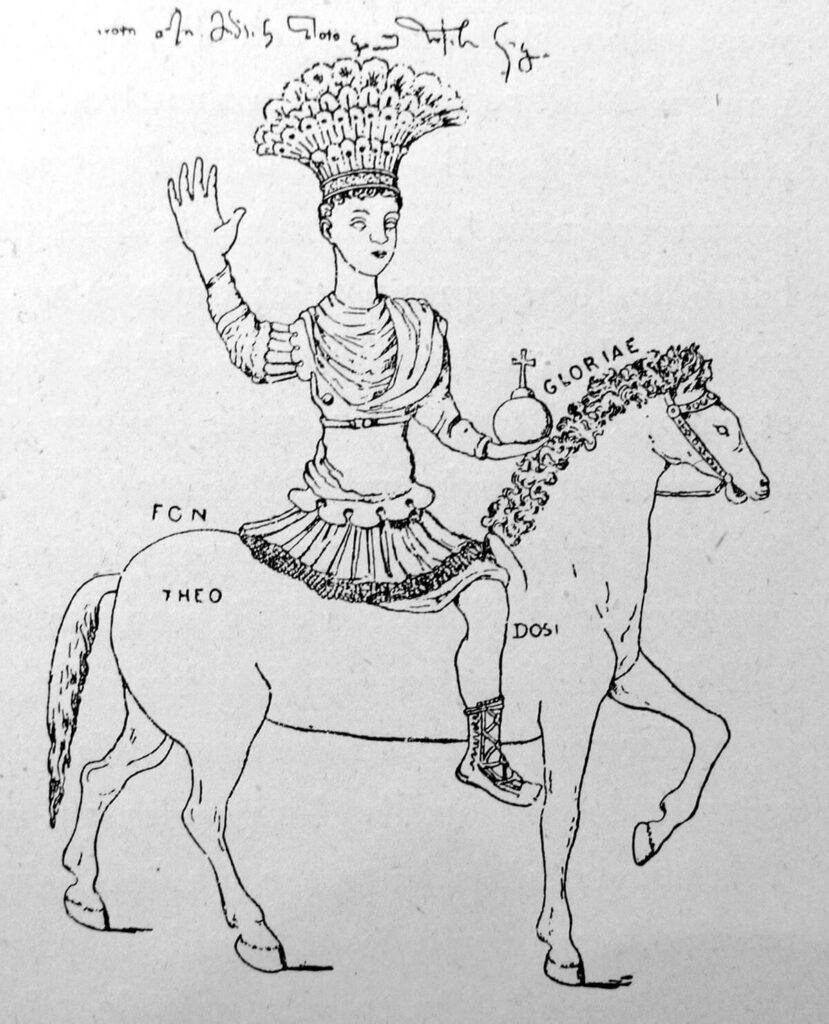

In Rome and in the new capital of the Bosphorus, the remains and memories of monumental ancient statuary were preserved. Statues of Constantine and his sons adorned the Capitoline Square and the façade of the Church of the Lateran in Rome. We know from written sources that Constantinople was also adorned with images of statues of Constantine. His colossal statue was located on the forum square, endowed with the attributes of the solar god, Sol Invictus. A statue of Justinien, erected on a column on the Augusteum square, presented the emperor on horseback as a Roman general, holding the globe in his left hand and his right hand raised in a “magic” gesture to repel the darkness. He wore a toupha, a curious helmet topped with a peacock feather plume, reserved for triumphs and which could derive from a Sassanid influence. The same crown was represented on a 10th-century textile, the Gunther shroud.

The “Theodosian Renaissance” of the late 4th century, the first revival of the Greek artistic past, produced works such as the statue of the young Valentinian II (375–392), discovered in Aphrodisias, Asia Minor, and dated to around 390. It is now housed in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul. The softness of the youthful face, the regularity of the features, and the wide folds of the toga that shape the body reflect the final echoes of ancient statuary. A bust of his brother Arcadius (383–404) follows the same style but with a more realistic approach.

The latest of these works is a colossal bronze statue of an anonymous emperor, found in Barletta, southern Italy. Sometimes attributed to Valentinian I (365–373), Marcian (450–458), or Heraclius (610–647), it represents the type of the victorious general. Yet the stiffened posture and robust realism of the face show only tenuous links with classical Roman art. Among the possible attributions, Marcian seems the most likely.

Two portraits of empresses have also survived: a small marble statue of Aelia Flacilla (died 388), wife of Theodosius I, kept in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris, and a head, probably later, sometimes attributed to Theodora, wife of Justinian, now located in the Castello Sforzesco in Milan.

More numerous are the portraits and statues of magistrates and dignitaries found in Asia Minor, in Ephesus or Aphrodisias, as well as elsewhere in the Byzantine world, including Thessaloniki and Constantinople. These works reflect the stylistic direction of the 5th century: sunken features with severe, distant, and contemplative expressions; heavy, rigid clothing that conceals the body; and forms worked on only three faces, leaving the back nearly raw, making them almost more like reliefs than fully sculpted statues. Yet some pieces still display remarkable sensitivity to modeling and fine detail, such as a 4th-century statue of a couple in the Museum of Thessaloniki.

Imperial Reliefs from the Early Byzantine times.

Some debris and drawings from the 16th and 17th centuries provide information about the last triumphal monuments, arches, and columns erected by emperors of the 4th and early 5th centuries. Adorned with numerous reliefs, the Arch of Constantine in Rome, built following the victory at the Milvian Bridge in 312, marks the beginning of Late Imperial sculpture in the West. The contrast with 3rd-century works is so striking that it prompts questions about this sudden shift in style. In Constantinople, remnants of the Column of Theodosius I, the base of the obelisk he erected in the Hippodrome, the Column of Marcian (450–457), and drawings of the Column of Arcadius, erected in 404, provide additional evidence.

The base of Theodosius’s obelisk in the Hippodrome is almost intact. It depicts key moments of official imperial ceremonies, arranged on the four faces of the marble block. On the northeast and southwest sides, the emperor is seated in his box, surrounded by dignitaries and his guard, presiding over the opening of the chariot races; the arch beneath his feet indicates the track’s exit. On the southeast side, he is shown standing, presenting the crown to the race’s winner. On the northwest side, he receives the homage of defeated barbarians. In two instances, he is depicted with his co-emperors: Valentinian II and Arcadius, his eldest son, and Honorius, his younger son. On the lower part of the base, a Greek inscription on the northwest side and a Latin inscription on the southeast side commemorate the monument’s foundation in 390. The remaining sides illustrate the work undertaken to erect the obelisk in the circus.

The imperial court itself elevated certain provincial tendencies to depict figures in a rigid and immobile manner—found in Egypt and north of the Alps—to the level of imperial art. Texts recount that Emperor Constantius II, during his entry into Rome in 357 on a triumphal chariot, astonished the populace with his immobile posture, “like a tower.” The emperor, as the representative of Christ on earth, had to embody the image of his heavenly sovereign. On coins, especially those issued in the East, he and his successors consistently present themselves in a rigid, frontal manner. It was in Constantinople, under the direct influence of the court, that this distinctly imperial and “Byzantine” style emerged.

The evolution of Christian Sculpture.

Christian sculpture did not produce works of the same magnitude as its Roman or Byzantine predecessors. Only a few examples survive in the round, such as statues of the Good Shepherd, Christ enthroned, and busts of the evangelists in the Museum of Istanbul. Among the Good Shepherd figures, a group of Greek origin from the late 4th century is not Christian: they depict simple shepherds carrying a ram on their shoulders, serving as table supports. A statue of Christ in the Museo Nazionale in Rome, from the second half of the 4th century, reflects a classicizing style seen in Rome and Milan.

Sarcophagi provide richer evidence for the evolution of Christian relief sculpture. They can be classified into several groups based on region of origin. Generally of average quality and more artisanal than artistic, they are nonetheless highly valuable for the abundant information they offer on early Christian iconography. Three main groups can be distinguished. The first, from Italy (excluding Ravenna), is the most numerous and of the highest quality, spanning the first half of the 3rd century to the 5th century and including Latin provinces such as Gaul, Spain, and North Africa. The second, from Constantinople and Asia Minor, emerges at the end of the 4th century. It is later and less homogeneous, with unity residing mainly in provenance rather than style. The third group, from Ravenna and regions under its influence, occupies a middle ground between the Latin West and the Greek East, appearing continuously from the late 4th century to the 7th century.

By the second half of the 5th and into the 6th century, symbolic motifs increasingly supplanted Christological scenes. Sheep or peacocks, representing apostles or the faithful, are juxtaposed with a chrisme enclosed in a triumphal crown or a cross bearing the alpha and omega, set atop the mound of paradise from which the four rivers flow. Occasionally, vases sprouting vine shoots surround a cross, symbolizing this paradisiacal world.

Beyond sarcophagi, figurative decoration appears on a limited number of ecclesiastical furnishings and architectural elements: ambos, chancels, doors, capitals, column shafts, architraves, and pediments. These objects are few, and their styles vary widely depending on region and period.

The Middle Byzantine Period.

Often considered the apogee of Byzantine art, sculpture remained a relatively minor decorative element compared to the mosaics and frescoes that adorned churches and palaces. By this period, sculpture in the round had entirely disappeared.

In the 10th and 11th centuries, church decorations applied to structural elements—capitals, column and pillar shafts, architraves, and cornices—underwent significant transformations. Stone and marble were sculpted, but surfaces remained flat and only lightly modeled. Flat relief bands highlighted the springing of vaults, both inside and outside (e.g., the Basilica of Skripou), and sometimes extended along the shafts of pilasters and pillars (e.g., the Church of Constantine Lips). Capitals preserved more of the craftsmanship characteristic of the 6th century. Chancel slabs and ambos were adorned with motifs spanning from northern Italy (Lombard art) to Syria (Umayyad art), largely drawing on antique traditions: vine or acanthus scrolls populated with animals, rosettes inscribed in medallions, and confronted peacocks.

By the 10th century, Islamic influence became increasingly evident. Motifs of Persian origin—the “Sassanid” fleuron, the simurgh (a winged creature with a peacock tail and a wolf’s head), peacocks, and heraldic eagles—appeared alongside decorative bands imitating Kufic script, permeating not only sculptural decoration but also ceramics and manuscripts. Theophilus’ (825–842) documented interest in Abbasid architecture may explain this sudden and pronounced Islamic influence in Byzantine art.

Sculpture in the Late Byzantine Period.

Byzantine sculpture in the late period largely adhered to the canons of the Middle Byzantine era, though Western influence occasionally became more pronounced.

Historical sources point to a renewed interest in sculpture among the upper echelons of Byzantine society, a trend likely encouraged by Emperor Michael VIII, who restored the Empire after recapturing Constantinople in 1261 and fostered a new antiquarian taste. In other parts of the Byzantine world, like in the Despotate of Epirus, sculpture also gained larger visibility, probably with the influence of Western art. The frequent use of inscriptions and monograms on sculptures indicates that patrons during the Palaiologan period regarded sculpture as an effective medium for expressing personal identity.

This era is also notable for the widespread use of spolia, particularly materials taken from Early Christian monuments. Such reuse reflected not only economic considerations but also deliberate political and aesthetic choices, with newly commissioned sculptures often designed to interact with carefully selected fragments from earlier periods.

Despite these influences, Late Byzantine sculpture demonstrates originality and remarkable synthetic flexibility. It also engages closely with monumental painting, with both arts complementing each other within the decorative programs of churches.

Notable examples of Byzantine Sculptures.

Byzantine sculpture, though often overshadowed by mosaics and frescoes, offers fascinating insights into the artistic and cultural priorities of the empire. The following examples showcase the diversity of styles, materials, and techniques, illustrating both the continuity of tradition and the innovations introduced over the centuries.

-

Eagle and hare closure slab from the middle Byzantine era in Thessaloniki

This stone slab was part of the closure slab from a church in Thessaloniki. It dates back to the 10th or 11th century. The middle Byzantine era was a period of prosperity and it can be felt in the artistic production. Many other similar sculptures of the time are showcasing myhtological animals, indicating that the…

Sources:

Nicholas Melvani , Late Byzantine Sculpture. (Studies in the Visual Cultures of the Middle Ages, 6). Turnhout: Brepols 2013.