The Middle Byzantine period

Byzantine historiography, developed by scholars since the 18th century, has traditionally divided Byzantine history into three phases: the early, middle, and late periods. The Middle Byzantine era extends from the 8th century, marking a major shift in the empire’s structure and organisation, to 1204, when the fall of Constantinople to the Crusaders shattered the empire, dealing a blow from which it never fully recovered. It is a period characterised both by intense struggles and by remarkable cultural achievements, notably the Macedonian Renaissance, which produced significant artistic and literary works, as well as the expansion of Orthodoxy in the Balkans and the Slavic-Russian world.

History of the Middle Byzantine period.

In the 7th century, the Byzantine Empire experienced a period of severe crisis. The devastating war against the Persians, the Slavic migrations in the Balkans, and the Arab invasions led to the collapse of classical urban life in most Byzantine cities and to the loss of significant parts of the empire. This period, which also saw the rise of Iconoclasm, is commonly referred to as the Byzantine Dark Age, marks the end of the Early Byzantine period.

Military recovery and end of the iconoclasm.

However, the Byzantine Empire managed to recover from near collapse. The Middle Byzantine period is often considered to begin with the end of the first phase of the Iconoclastic Controversy in 787 and the full restoration of icons in 843. The end of this religious turmoil allowed for a revival of religious art and a blossoming of Byzantine culture. Iconography, mosaics, and church architecture reached new heights during this time, reflecting the restored unity between Church and state. It was also a turning point in the empire’s resistance to foreign invasions. The iconoclast emperors had managed to stabilise the military situation and push back external threats. This military resurgence was closely connected to the reorganisation of the administration and army and the implementation of the theme system. This system proved both flexible and efficient, and played a significant part in the long-term resilience of the empire.

The Macedonian dynasty.

Under the Macedonian dynasty (867–1056), the Byzantine Empire enjoyed a prolonged period of political stability and strategic consolidation that laid the foundations for its resurgence as a major Mediterranean power. Founded by Basil I, whose ascent from modest origins reshaped imperial ideology, the dynasty implemented important administrative and legal reforms, including the Basilika, which rationalised and updated the empire’s legal framework. The central government strengthened its control over the provinces, refining the theme system and improving tax collection, which in turn reinforced the state’s capacity to sustain large, professionalised armies.

Militarily, the Macedonian period was defined by a series of successful campaigns led by emperors and generals such as Basil I, Nikephoros Phokas, John Tzimiskes, and Basil II. These victories reversed earlier territorial losses and expanded Byzantine authority across key regions. The reconquest of Crete, Cyprus, and parts of northern Syria secured the empire’s eastern frontiers, while in the Balkans, Basil II’s decisive defeat of the Bulgarian Empire in 1018 brought the entire region under Byzantine rule. In Italy, the empire regained influence in the south and maintained a strategic presence despite growing Norman pressure. Diplomatically, the Macedonians forged advantageous alliances and used dynastic marriages to stabilise relationships with neighbouring states, including the Rus’, Armenians, and Western powers.

This political and military strength, supported by a relatively stable economic base, enabled the empire to reassert itself as a dominant force in southeastern Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. Although the Macedonian dynasty eventually gave way to weaker rulers in the mid-11th century, its long period of effective governance, territorial expansion, and institutional reinforcement played a decisive role in shaping the empire’s trajectory and left a legacy of restored confidence and central authority.

Mantzikert and the Komnenian dynasty.

Significant challenges, particularly from the rise of new powers such as the Seljuk Turks in the east and the Normans in the west, emerged as the Macedonian dynasty came to an end. The Seljuks dealt a major blow to the empire at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. Although the defeat itself was not irrecoverable, the capture of the emperor and the subsequent struggle for power, during which pretenders withdrew troops from Anatolia in an attempt to seize the crown, led to the loss of most of Asia Minor to the Seljuks. This disastrous situation was worsened by the growing ambitions of the Normans at the same time and became one of the triggers that led to the First Crusade in the West.

Alexios Komnenos managed to stabilise the situation in Anatolia, though a large part of the region would never be recovered by the Byzantines, and keep the Normans in check. The Komnenian dynasty marked the final peak of Byzantium as a political power. However, it also favoured the nobility and concentrated authority in the hands of the extended Komnenian family, while the peasantry increasingly became dependent on the aristocracy or monastic estates, developments that weakened the empire in the long term.

The turning point at the end of the 12th century and the Fourth Crusade.

The late 12th century saw intense struggles for the throne among powerful noble families, especially the Doukai and the Angeloi. These conflicts ultimately paved the way for the Fourth Crusade, which was initially intended to reinstate the deposed Emperor Isaac II Angelos (alongside his son, the future Alexios IV), but instead resulted in the capture and looting of Constantinople by the Crusaders themselves. The fall of the capital, in addition to being a devastating cultural blow for the Byzantines, brought chaos and created a fragmented political landscape in the Eastern Mediterranean, marking the end of the Middle Byzantine period.

Nevertheless, it remains a time of significant cultural and political revitalisation, leaving a profound and lasting impact on the medieval Mediterranean and the Orthodox Christian world. Although the empire’s resources were more limited than in the Early Byzantine period, the art and architecture of this era stand as remarkable testaments to the splendour and creativity that flourished during this time.

Society, cities, and economy.

During the Middle Byzantine period, the empire remained predominantly agrarian, with smallholding peasants forming the backbone of both the economy and the military through the theme system. Over time, however, large aristocratic estates and monastic properties expanded, gradually undermining the traditional free peasantry and shifting wealth and influence toward elite families. Urban life revived after the crises of the 7th and 8th centuries, with cities such as Constantinople, Thessaloniki, and Trebizond flourishing as centres of administration, craftsmanship, and long-distance trade.

The economy benefited from Byzantium’s strategic position between Europe and Asia: merchants traded silk, spices, metals, and luxury goods, while state control over key industries, especially silk production, ensured significant revenue. Despite periodic disruptions from warfare, the Middle Byzantine period was generally marked by economic recovery, demographic growth, and cultural dynamism, forming the foundation of the empire’s political resurgence between the 9th and 11th centuries.

Art and Architecture during the Middle Byzantine period.

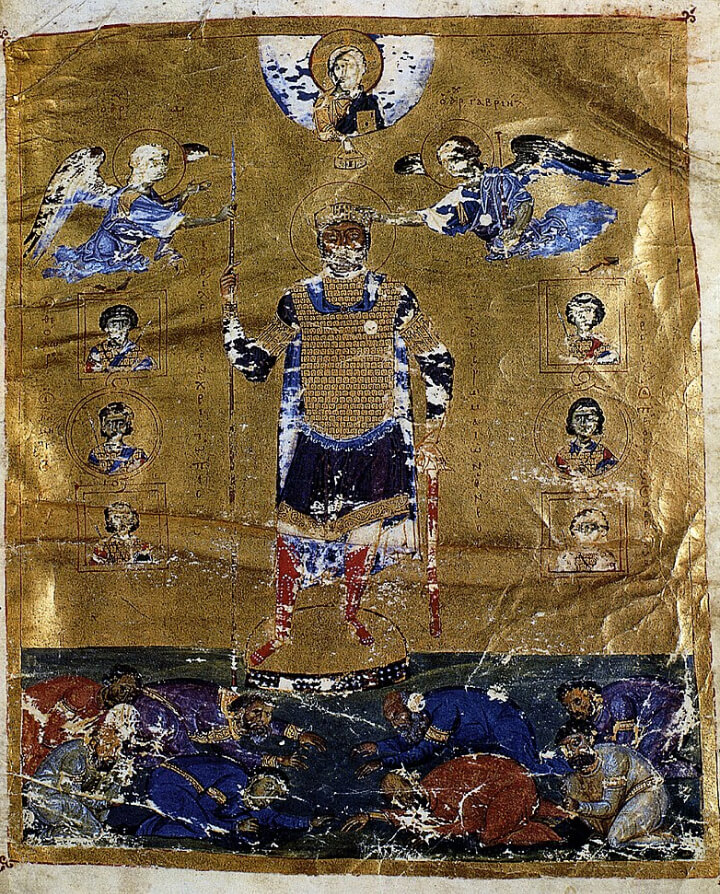

Middle Byzantine art and architecture reached a remarkable level of refinement, reflecting both the religious renewal that followed the end of Iconoclasm and the growing confidence of an expanding empire. Church architecture evolved toward more complex, centrally planned structures, especially the cross-in-square church, adorned with rich mosaic and fresco programs that emphasised theological symbolism and imperial piety. Icon painting flourished, developing a more spiritualised and expressive style that became foundational for later Orthodox artistic traditions. Manuscript illumination also thrived, blending classical artistic heritage with Christian themes; one of the most notable witnesses to this intellectual and artistic milieu is Anna Komnena, whose Alexiad not only provides invaluable historical insight but was itself produced in an environment that fostered literary sophistication and the patronage of the arts. Court workshops, monastic scriptoria, and major urban centres such as Constantinople and Thessaloniki had a central role in shaping a visual culture that spread across the Balkans, the Caucasus, and the Slavic world. The result was a vibrant artistic landscape whose influence endured long after the political power of Byzantium began to fade.