The Imperial Power in Byzantium

Imperial power in Byzantium was a remarkable synthesis of Roman legal traditions, Christian theology, and Eastern autocratic principles. Rooted in the legacy of the Roman Empire, the Byzantine concept of authority was redefined by its Christian foundation, which portrayed the emperor as God’s chosen representative on Earth. This unique position granted the emperor not only secular authority but also significant influence over the Church and its clergy, including the appointment of patriarchs and the oversight of ecclesiastical affairs. By unifying political and spiritual power, the emperor embodied a divine mandate in a way unparalleled in history, reinforcing the centrality of imperial authority in every aspect of Byzantine life.

Centralized power in Byzantium was maintained through a combination of legal frameworks and a highly organized bureaucracy, with a pivotal role played by the capital. Constantinople was the political, economic, and spiritual heart of the empire, as well as the center of its bureaucracy. From this hub, the emperor directed an extensive provincial administration tasked with maintaining order, collecting taxes, and enforcing imperial decrees across the vast territories of the empire. The balance between the central authority of Constantinople and the effective management of the provinces was key to sustaining the empire’s cohesion. Despite challenges such as internal revolts and external threats, the Byzantine system of imperial power proved its strength by enduring for over a millennium. Nonetheless, it adapted and evolved to meet the needs of an ever-changing international context and saw the rise of regional powers during the late Byzantine period. With the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and Trebizond in 1461, Byzantine imperial power disappeared, though its ideals and symbolism persisted in the Balkans and Russia.

To facilitate your navigation through this comprehensive article, you will find below links to the main sections.

The Roman roots of the Byzantine imperial power.

Theological foundations of the imperial power.

The pillars of imperial power: Central bureaucracy and provincial administration.

Military power and economic foundations.

The Roman roots of the Byzantine imperial power.

The transition from Roman to Byzantine concepts of authority marked a profound redefinition of imperial power, blending Roman political traditions with the emerging Christian faith. In the Roman Empire, the emperor was seen as the supreme ruler. He also held the title of pontifex maximus, the chief priest of the state religion, which placed him at the head of the religious hierarchy. This role was crucial in maintaining the favor of the gods and ensuring the stability of the empire. Nonetheless, the emperor’s authority was rooted in Roman law, military power, while his role as pontifex maximus was more about upholding traditional Roman religious practices rather than establishing a direct spiritual leadership over the people.

However, with the rise of Christianity and the establishment of the Eastern Roman Empire, the emperor’s role underwent a significant transformation. Constantine’s conversion to Christianity and his subsequent efforts to align the imperial office with Christian teachings reshaped the very essence of Roman imperial authority. By convening the First Council of Nicaea in 325, Constantine established a precedent for imperial involvement in religious matters, asserting the emperor’s authority over the Church and reinforcing the idea that the emperor was divinely chosen to lead both the empire and its Christian population. From Constantine onward, in the Byzantine tradition, emperors were not only secular rulers but also God’s representatives on Earth.

Constantine also used Christian symbolism to solidify his power. He famously adopted the Christian Chi-Rho symbol and incorporated it into imperial imagery, aligning his rule with the divine. This shift was also linked to the earlier Roman tradition of sol invictus, the “Unconquered Sun,” a pagan deity that symbolized the emperor’s divine protection and invincibility. Constantine’s adoption of Christianity did not completely discard this symbolism; instead, he reinterpreted the sol invictus as a symbol of Christ, positioning himself as the “new sun” of the Christian world.

Thus, Constantine’s reign marked the beginning of a new era in which the emperor was not only the earthly ruler but also the spiritual leader, a dual role that would define Byzantine imperial power for centuries to come. Byzantine emperors, following Constantine, held both secular and spiritual authority, defining the concept of imperial power in Byzantium.

Theological foundations of the imperial power in the Eastern Roman Empire and Byzantium.

In Byzantine ideology, the emperor was regarded as “Christ’s vicegerent on Earth,” a divinely appointed ruler entrusted with governing both the secular and spiritual realms. This belief positioned the emperor as a crucial intermediary between God and the empire, responsible for maintaining divine order and ensuring the prosperity of the Christian state. The emperor’s authority was thus not merely political but carried profound theological significance, as he was seen as carrying out God’s will on Earth.

The Church played a central role in legitimizing imperial power, reinforcing the emperor’s divine mandate. Through rituals such as the coronation ceremony, conducted by the Patriarch of Constantinople, the Church sanctified the emperor’s rule, publicly affirming his status as God’s chosen representative. This relationship between the Church and the emperor was symbiotic; while the Church provided religious legitimacy, the emperor protected and promoted the Church’s interests, often intervening in theological disputes and shaping ecclesiastical policy.

This fusion of spiritual and temporal authority underpinned Byzantine imperial power, creating a unique model of governance where the emperor was both a ruler and a spiritual leader, reinforcing the unity of church and state within the empire.

The pillars of imperial power.

Central bureaucracy and provincial administration.

Byzantine imperial power relied on a highly organized bureaucracy, a sophisticated legal framework, and an efficient provincial administration to govern its vast territories. The legal system, epitomized by Justinian’s Code (Corpus Juris Civilis), provided a unifying structure for the empire, standardizing laws and ensuring the emperor’s decrees were implemented across diverse regions. This codification not only reinforced the emperor’s authority but also became a foundational influence on legal traditions in Europe and beyond, extended and adapted by subsequent emperors, notably Basil I and Leo VI, whose Basilika modernized and refined the legal corpus.

Key institutions such as the Senate and the imperial court played pivotal roles in the administration of the empire. While the Byzantine Senate had diminished in power compared to its Roman predecessor and continued to lose influence throughout Byzantine history, it remained an advisory body composed of influential figures, serving as a symbolic link to the empire’s Roman heritage. Its prestige perdured during the Early and Middle eras, and was especially vivid in the 11th and 12th centuries.

The court, on the other hand, was the epicenter of Byzantine governance, where the emperor presided over state affairs and ceremonial functions. It was staffed by a complex hierarchy of officials, including eunuchs, who often held critical roles in administration. Among the most powerful ministers were the logothetes (ministers), who managed finances, military logistics, and diplomacy. In the later period, the role of the mesazōn (chief intermediary or chancellor) emerged as particularly significant, acting as a primary advisor to the emperor.

In the provinces, the administration was structured to maintain order and ensure the flow of taxes and resources to the capital. Governors, often appointed by the emperor, oversaw local governance and reported directly to the central bureaucracy. This integration of provincial administration with imperial authority was critical for maintaining the cohesion of the empire. Facing numerous challenges, the provincial administration was revised in the 7th century with the establishment of the theme system, which combined military and civilian authority under a strategos (military governor) to enhance defense and governance efficiency.

As the empire shrank during the later Byzantine period, the provincial system became more fragmented. Semi-independent rulers, such as the despots of the Despotate of the Morea, governed key territories while still nominally recognizing the emperor’s authority. This shift reflected the declining resources of the empire and the increasing reliance on regional power centers to maintain control over remaining territories.

Together, the bureaucracy, legal system, and administrative institutions exemplified the centralized and enduring nature of Byzantine imperial power, adapting to the empire’s changing needs while preserving its legacy as a model of governance.

Military power and economic foundations.

The strength of Byzantine imperial power was deeply connected to its military campaigns and territorial expansion, which reinforced the empire’s prestige and ensured its survival. Successful military campaigns, such as those led by Justinian I in the 6th century or Basil II in the 11th century, not only expanded the empire’s borders but also brought wealth, resources, and stability to the state. These conquests were often accompanied by strategic efforts to integrate newly acquired territories into the Byzantine administrative framework, ensuring that imperial authority was firmly established across the empire.

The Byzantine army played a decisive role in imperial politics, often determining succession and the rise of new emperors, as powerful generals or elite troops could make or unmake rulers, enabling usurpators to seize the throne and shaping the course of the empire through their backing or opposition.

The sustainability of the defensive efforts or agressive military campaigns as a whole depended on a robust economic foundation. Taxes, trade, and land ownership were critical elements that defined the capacity of the empire to resist and expand. The Byzantine tax system was highly organized, with a combination of land taxes, trade duties, and personal levies ensuring a steady flow of revenue to the imperial treasury.

Taxation was rigorously enforced by the central bureaucracy, with revenues used to fund military expenditures, infrastructure projects, and administrative costs. Land ownership was another cornerstone of Byzantine economic power. Large estates, often owned by the Church, the imperial family, or wealthy aristocrats, produced agricultural surplus that supported both the population and the army. However, the concentration of land in the hands of powerful magnates posed challenges to central authority, particularly in the later Byzantine period. Efforts to curb the power of these landowners, such as the legislation enacted by emperors like Basil II, were aimed at preserving the fiscal and social stability of the empire.

Trade also played a crucial role in sustaining imperial power. Constantinople’s strategic position as a crossroads of Europe and Asia made it a hub for international commerce, with goods from as far as China, India, and northern Europe passing through its markets. The empire’s control over key trade routes, such as the Silk Road and the Black Sea, provided a significant source of income and reinforced its geopolitical influence.

Economic decline and the slow erosion of Byzantine power.

From the 11th century onward, the Byzantine Empire began to experience a slow but steady economic decline, which paralleled the weakening of its territorial and political power. While the empire had once been a dominant economic force in the Mediterranean, a combination of internal and external factors gradually eroded its prosperity.

One of the key developments in this period was the increasing privileges granted to foreign powers, particularly the Latin states and Western merchants. Following the First Crusade (1096-1099), Western European merchants gained significant economic advantages in Byzantine trade, with the Venetian, Genoese, and Pisan merchants receiving trading privileges that allowed them to control key ports and trade routes. The privilegia granted to these Latin merchants, including favorable tax rates and the establishment of trade monopolies, undermined the position of Byzantine merchants. As Western merchants flourished, the Byzantine merchant class slowly declined, struggling to compete with the influx of foreign goods and capital.

This economic shift had broader consequences for the empire. With the growing dominance of foreign merchants, the Byzantine economy became increasingly dependent on trade with the West, and the empire’s control over vital trade routes was gradually diminished. The once-thriving markets of Constantinople, which had been a hub for goods from across Asia and Europe, began to lose their central role in international commerce. This not only weakened the economic foundation of the empire but also increased its vulnerability to external pressures.

The decline of the Byzantine merchant class was accompanied by a general deterioration in the empire’s military and administrative systems. The loss of economic vitality, combined with the financial burden of defending an ever-shrinking empire, led to the depletion of state resources. As the Byzantine elite increasingly relied on foreign mercenaries and regional powers to defend the empire’s borders, the central authority of Constantinople weakened further.

In the later Byzantine period, particularly during the 13th and 14th centuries, the empire’s economic decline mirrored its territorial losses. The Fourth Crusade (1204) was a devastating blow to the empire, as Constantinople was sacked and large portions of its wealth, including religious relics and treasures, were plundered. While the Byzantines regained the city in 1261, the empire never fully recovered from this loss. The Latin presence in the region continued to undermine Byzantine economic and political power, as Western merchants and states continued to exert influence over key economic sectors.

Furthermore, the decline of agricultural production, largely due to the loss of fertile lands to invading forces and the fragmentation of the empire’s once expansive territory, further exacerbated the financial difficulties of the Byzantine state. As a result, the empire became increasingly dependent on external loans and resources, particularly from Western Europe, but these financial arrangements only deepened its dependence on foreign powers and further eroded its independence.

In the final centuries of the Byzantine Empire, the weakening economy, compounded by the loss of key territories and the rise of powerful regional elites, contributed to the empire’s collapse. By the 15th century, the once-thriving Byzantine economy had been reduced to a shadow of its former self, with Constantinople itself isolated and surrounded by increasingly hostile powers. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 marked the ultimate consequence of these centuries of economic and political decline, as the once-mighty empire was overtaken by the Ottomans, who had capitalized on the weakening of Byzantine power.

Thus, the slow but steady decline of the Byzantine economy, fueled by the rise of foreign competition, the weakening of the imperial authority, and the erosion of its territorial holdings, played a crucial role in the eventual collapse of the empire. Despite its earlier successes, the Byzantine Empire could not maintain its economic and political dominance in the face of growing external challenges and internal inefficiencies, leading to its ultimate fall.

Cultural projection of the imperial power in Byzantium.

In Byzantium, the emperor’s authority was not only maintained through political and military power but also reinforced through art, architecture, and ritual. These cultural and religious expressions played a crucial role in projecting imperial power and legitimizing the emperor’s rule, establishing a visible and tangible connection between the divine and the earthly realms.

Material expression of imperial sovereignty in Art and Iconography.

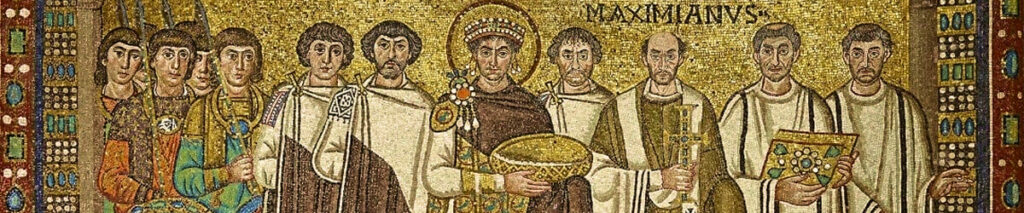

Byzantine art was a powerful tool for conveying the emperor’s divine and secular authority. One of the most striking features of imperial iconography was the representation of emperors with halos. The halo, traditionally used to represent saints and Christ, was applied to the emperor’s image to signify that they were not only earthly rulers but also divinely chosen representatives of God. This association between the emperor and the divine was a core aspect of Byzantine ideology. Emperors were often depicted with halos in various artistic forms, including icons, mosaics, and frescoes, which were used extensively in churches, palaces, and public spaces.

Monumental statues of emperors were a significant form of imperial representation during earlier periods, but by the 6th or 7th century, this practice began to disappear. Instead, emperors were represented in more symbolic forms through icons and mosaics, where their divine status was highlighted, often alongside Christ or the Virgin Mary. Such depictions were not merely decorative; they were designed to reinforce the emperor’s authority and sanctity in the eyes of the people. The most famous examples of imperial iconography can be found in the mosaics of the Hagia Sophia, where the emperor was frequently depicted in the company of Christ or the Virgin Mary, emphasizing his role as God’s representative on Earth.

Coins were also a vital instrument in the visual representation of imperial power. Byzantine coins bore the image(s) of the emperor(s), further reinforcing his presence throughout the empire. These coins were not only a practical means of exchange but also served as a constant reminder of the emperor’s divinely sanctioned authority. The images on the coins often depicted the emperor in a strong and regal manner, with symbols of power, ensuring that even the humblest subjects would be reminded of the emperor’s omnipresence.

Manifestation of imperial ideology through Architecture.

Architecture was another key medium for projecting imperial power. One of the most striking examples of Byzantine imperial power expressed through architecture is the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Originally built by Emperor Justinian in the 6th century, the Hagia Sophia was a symbol of imperial grandeur and religious legitimacy. Its massive dome, which seemed to float miraculously above the central nave, was a visual representation of the emperor’s divine mandate. The scale and design of the building emphasized the emperor’s power, and the church’s use as a place for imperial coronations, celebrations, and rituals further reinforced the connection between the emperor and the divine.

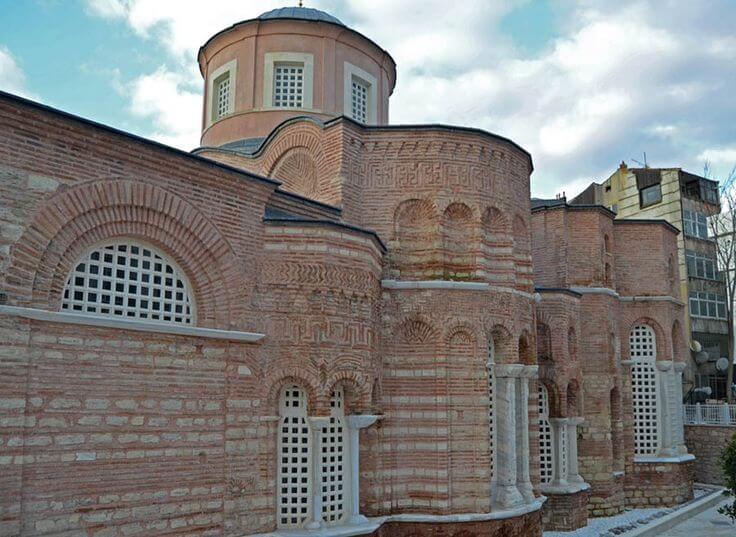

Other key imperial buildings include the Church of the Holy Apostles, one of the most important religious edifices of Constantinople after the Hagia Sophia, which has not survived to the present day. The church, rebuilt by Justinian on a grand scale, served as the imperial mausoleum, housing the tombs of emperors and empresses from the early Byzantine period until the late 11th century. Inside its grand cruciform structure stood the porphyry sarcophagi of the empire’s greatest rulers, including Constantine the Great, Justinian I, and many of their successors, as well as those of empresses and other members of the imperial family. The church also functioned as the necropolis of the Patriarchs of Constantinople, reinforcing the symbolic union of imperial and spiritual authority. This intertwining of monarchy and faith reflected the Byzantine belief that the emperor’s power was divinely ordained and enduring, extending even beyond death. However, after the end of the Macedonian dynasty in the late 11th century, the church’s role as an imperial necropolis gradually declined and ultimately ceased in the following centuries.

From the 10th century onwards, emperors began to establish dynastic religious foundations to serve as burial sites for themselves and their families. The first example was created by Romanos Lekapenos (920-944) with the construction of the Myrelaion, built on the site of his family palace in Constantinople. This complex included a church—erected over a former rotunda—and an adjoining palace, later converted into a monastery. This model became increasingly common after the Macedonian dynasty, as emperors abandoned burial in the Holy Apostles.

John II Komnenos (1118-1143), for instance, founded the Christ Pantocrator complex, conceived as an imperial mausoleum to house the tombs of himself and his family. Such foundations served imperial power by linking the ruling dynasty to newly consecrated spaces within the capital. These monuments were not only expressions of political authority but also emblems of dynastic continuity across generations.

The situation was less clear under the Palaiologoi. Many emperors died far from Constantinople, and despite some short-lived efforts to create new imperial mausoleums, these projects often failed to achieve lasting significance. The Monastery of Lips, which functioned as a secondary imperial burial site and hosted the tomb of only one emperor, was conceived more as a family necropolis than as a true imperial one.

The imperial palaces were maybe the most critical architectural symbols of imperial power. The Great Palace was during centuries the heart of the imperial power, before it moved in the Middle Byzantine times to the Blachernae Palace, located near the Blachernae district of Constantinople. It was both a residence for the emperor and a center for political and military decision-making. The palace, which housed the imperial family and court, was a focal point for imperial rituals and public appearances, further cementing the emperor’s dominance over both the political and spiritual life of the empire. The architectural design of these palaces and religious structures emphasized the emperor’s central role and his connection to both the state and the divine, projecting his authority through monumental spaces that were awe-inspiring and sacred.

After 1204 and the shattering of the Byzantine world, several regional political centers emerged. Imperial residences were built in the Empire of Nicaea, where the winter residence at Nymphaion still stands today, as well as in Trebizond, Arta, and in Mystras, with the Despot’s Palace. In Constantinople, reclaimed in 1261, the Grand Palace was largely left in ruins, and the imperial court resided in the Blachernae Palace, although on a smaller scale than in previous centuries.

Rituals and Ceremonies.

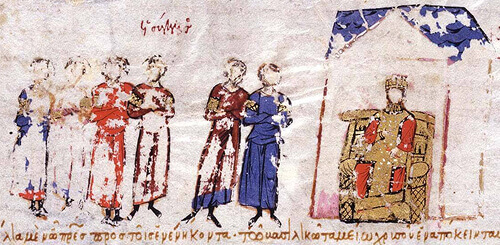

The rituals and ceremonies surrounding the emperor were another essential way of asserting imperial authority. Public processions, coronations, and appearances were meticulously staged to emphasize the emperor’s divinely ordained rule. The most important of these ceremonies was the emperor’s coronation, during which the emperor was crowned with sacred regalia, symbolizing both his temporal and spiritual power. These events were often accompanied by grand displays of wealth and military might, further underlining the emperor’s supreme position.

Public processions, such as those during religious festivals or military victories, also served to reinforce imperial power. The emperor would often appear before the public, lavishly dressed and surrounded by his court, military leaders, and officials. These events were designed to remind the people of the emperor’s role as their protector and ruler. In addition to reinforcing the emperor’s authority, these public displays were meant to demonstrate the strength and unity of the empire under his leadership.

The emperor’s participation in religious ceremonies, such as attending mass or leading prayers in the Hagia Sophia, was another way in which the emperor’s spiritual authority was reinforced. By taking part in these rituals, the emperor was seen not only as the ruler of the empire but also as a key figure in the religious life of the Byzantine people, mediating between God and the state. These public appearances allowed the emperor to maintain a direct connection with the divine, further solidifying his power and legitimacy.

Together, art, architecture, and rituals were integral to the Byzantine emperor’s ability to maintain and project authority. Through these mediums, the emperor’s power was not only asserted in the realm of politics and military conquest but also in the spiritual and cultural life of the empire. They served as constant reminders to the people of the emperor’s divinely sanctioned rule and the central role he played in both the earthly and heavenly domains.

Succession crises, revolts, and invasions: Evolution of imperial power and its decline.

Byzantine imperial power, despite its centralized structure and divine legitimacy, was frequently challenged by internal and external forces. Over the centuries, succession crises, revolts, and invasions destabilized the empire, forcing the imperial system to evolve in response to these challenges. While these events did not immediately lead to the collapse of the Byzantine Empire, they contributed significantly to its eventual decline.

Succession Crises.

One of the most persistent challenges to Byzantine imperial power was the issue of succession. Emperors often associated their heirs as co-emperors to secure the succession or sought to legitimize their rule by marrying the former empress or a prominent female member of the previous dynasty. However, the lack of a clear, universally accepted system of succession frequently led to power struggles, with competing factions and rival claimants to the throne.

These crises were particularly destabilizing as they not only threatened the continuity of leadership but also weakened the central authority of the emperor. In the absence of a stable system of inheritance, rival military leaders, aristocrats, and even religious figures would frequently intervene in the imperial succession process. These internal conflicts often resulted in civil wars, weakening the empire’s ability to defend itself against external threats and manage its vast territories.

One of the most notable examples of a succession crisis occurred in the 11th century, with the extinction of the Macedonian dynasty. This period of uncertainty, combined with military defeats, particularly by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, marked the beginning of the empire’s long-term decline. While the Komnenos managed to reverse the tide for one century, the end of the 11th century and the fall of the Komnenian dynasty were marked by competition among families for the imperial throne, leading to the devastating capture of Constantinople by the Latins in 1204.

Revolts and Internal Instability.

Revolts and internal strife were persistent challenges to Byzantine imperial authority. As the empire’s territories expanded and administration became more complex, local power structures increasingly challenged the central authority. Provincial governors, military commanders, and wealthy aristocrats sometimes rebelled, either to seize the throne or to gain greater autonomy. These uprisings, often fueled by economic hardship, regional rivalries, religious disputes and dissatisfaction with imperial policies, further eroded the emperor’s control and tested the resilience of the state.

The Iconoclast Controversy (8th–9th centuries) is perhaps the most famous religious dispute in Byzantine history. Centered on the veneration of religious images, it illustrates how ideological divisions could exacerbate political instability, as factions supporting either the iconoclast (image-smashing) policies of the emperors or the iconophile (image-venerating) stance of the church created deep social and political fractures. However, this was far from the only religious or moral controversy to affect imperial authority. Earlier, the Monophysite controversy of the 5th and 6th centuries divided Chalcedonian and Monophysite Christians, provoking unrest in provinces such as Egypt and Syria. Later, in the 9th–10th centuries, emperors such as Leo VI the Wise faced opposition over his fourth marriage, known as the Tetragamy controversy, which challenged canonical law and drew criticism from the patriarch and clergy. Even in later centuries, theological debates—such as the Hesychast controversy in the 14th century or the attempts at church union in the 15th century—continued to test the emperor’s authority. Across these episodes, religious and moral disputes repeatedly strained imperial prestige, undermined internal cohesion, and at times limited the empire’s capacity to respond effectively to external threats.

Religious sects also contributed to instability. The Paulicians, a dualist Christian sect in eastern Anatolia, staged repeated rebellions in the 9th and 10th centuries, sometimes aligning with Arab forces. Their insurgencies combined religious dissent with military threat, highlighting the intersection of faith and politics in undermining imperial authority.

Military rebellions provided some of the most acute crises. The revolt of Thomas the Slav (821–823), for example, mobilized a massive army and fleet against Emperor Michael II and nearly captured Constantinople. In the late 10th century, Bardas Skleros (976–979) and Bardas Phokas the Younger (987–989) led large-scale uprisings in Anatolia against Emperor Basil II, drawing support from powerful provincial aristocrats. These revolts demonstrated the enormous influence of regional military elites and forced emperors to rely on loyal mercenaries, including the Varangian Guard, to secure their rule.

Internal strife continued into the late Byzantine period. During the Palaiologan era, civil wars between co-emperors—most notably John V Palaiologos versus John VI Kantakouzenos (1341–1347)—and revolts by aristocratic families in Thessalonica, the Morea, and Asia Minor further fragmented imperial authority and made it even more difficult to resist the advancing Turks.

Together, these examples illustrate that Byzantine emperors were constantly beset by internal threats, from ideological disputes and religious schisms to military revolts and aristocratic rebellions. Such persistent unrest strained the empire’s resources, undermined central authority, and hindered its ability to project power abroad, leaving it vulnerable to external enemies and contributing decisively to its long-term decline.

Invasions and External Threats.

Byzantine imperial power also faced significant challenges from external invasions. The empire’s strategic location made it a target for numerous incursions by foreign powers. From the long and devastating wars against the Slavs, Avars, and Sassanid Persians, and the early Arab conquests, to later conflicts with the Seljuks and Ottomans, the ambitions of the Normans, Crusaders, and Italian republics, and the rising powers in the Balkans, such as the Bulgars and Serbians, the Byzantine Empire’s territorial integrity was constantly threatened by forces beyond its borders.

The Arab expansion in the 7th and 8th centuries resulted in the largest territorial losses the empire ever experienced, including Egypt, Syria, and North Africa, regions crucial to its economy and military strength. The Seljuk Turks dealt a crushing blow at the Battle of Manzikert (1071), leading to the loss of much of Anatolia, the empire’s agricultural heartland, and again challenged the empire at the Battle of Myriokephalon (1176), which halted Byzantine attempts to recover central Anatolia. Later, the invasions of the Normans in the late 12th century and the Fourth Crusade in the early 13th century further weakened the empire, culminating in the sack of Constantinople in 1204 and the fragmentation of Byzantine rule.

These external invasions, coupled with internal instability, significantly weakened the power of the emperor. The loss of crucial territories diminished the empire’s resources, making it more difficult to maintain a strong military and efficient administration. In the later period, the Byzantine Empire’s shrinking size and diminished resources further exacerbated its decline, as it struggled to repel successive waves of invaders and contend with the rise of powerful regional states.

Decline and evolution of Byzantine imperial power.

Byzantine emperors faced a long history of challenges, including succession disputes, aristocratic revolts, and external invasions. These pressures forced the empire to continually adapt its political and military structures. In the early and middle Byzantine periods, imperial authority relied heavily on a combination of universalist claims, centralized bureaucracy, and the mobilization of a peasant-soldier base organized through the theme system, which allowed the emperor to maintain direct control over both military and civil affairs. Over time, particularly during the Komnenian dynasty (1081–1185), the structure of power shifted: emperors increasingly based authority on membership in the imperial lineage, securing loyalty through familial networks and dynastic legitimacy rather than broad popular military service. The professional peasant-soldier class gradually disappeared, replaced by prince-led contingents, mercenary forces, and private retinues.

By the Palaiologan period (1261–1453), Byzantine rulers confronted a radically altered political landscape. Imperial authority was largely confined to Constantinople and a few outlying territories, and emperors relied heavily on mercenary armies, alliances with regional powers, and a decentralized provincial administration to maintain control. With the empire reduced and weakened, a crucial shift occurred: the claim to universal imperial authority, which had underpinned Byzantine ideology for over a millennium, could no longer be realistically maintained. The former wealth, ceremonial splendor, and luxurious lifestyle of the imperial court had greatly diminished, reflecting the empire’s declining economic and political resources. Instead, the emperor’s role became more pragmatic and defensive, focused on preserving the remaining territories, maintaining internal cohesion, and asserting legitimacy, even as the empire’s resources, territory, and influence were increasingly constrained.

The enduring legacy of Byzantine Imperial Power.

Despite its decline, the Byzantine imperial model had a profound and lasting impact on global political culture. The emperor, as both secular ruler and divine representative, wielded supreme authority supported by a complex bureaucracy, legal codification, and centralized administration. The fusion of Roman political structures with Christian ideology created a model of governance that emphasized divine legitimacy, ceremonial authority, and institutional continuity.

This imperial idea influenced subsequent powers across Europe and beyond. The Holy Roman Empire adopted Byzantine ceremonial and political models to reinforce the sacral authority of its emperors. In Russia, the Moscow rulers claimed the title of “Tsar” and the mantle of the Byzantine imperial legacy after the fall of Constantinople, viewing themselves as heirs to the Orthodox Christian empire. Even the Ottoman sultans drew on Byzantine administrative and ceremonial practices, adapting aspects of court protocol, bureaucracy, and palace symbolism to legitimize their rule over a multi-ethnic empire.

Monumental architecture, religious rituals, art, and iconography served as enduring tools to project imperial authority, while provincial administration and court bureaucracy provided a framework for governance that inspired successive empires. Though the Byzantine Empire ultimately fell, its conception of centralized, divinely sanctioned imperial power endured, shaping the political and cultural landscapes of Europe, the Middle East, and beyond for centuries.