The Byzantine Castle of Nymphaion (Nif): A Laskarid Fortress

Only ruins remain today of the castle of Nif (ancient Nymphaion or Nympheum), but in Byzantine times, it was one of the most important fortresses of Lydia in western Anatolia. Archaeological surveys have revealed traces of earlier periods, especially the walls at the base of the north gates, but most visible structures date from the medieval times. Scholars attribute much of the fortifications to the Laskarid dynasty (add date). During this period, the rulers of the Empire of Nicaea heavily fortified their domains to resist the growing threat of the Turks, which the Byzantines managed to do successfully until 1315, when the western policy of the Palaiologus dynasty led to the fall of most of Asia Minor, ending the Byzantine rule over Nymphaion.

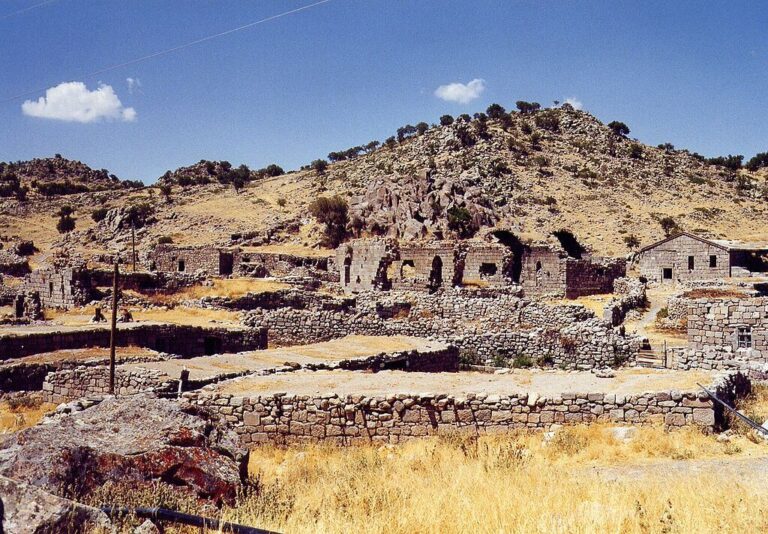

The ruins of Nymphaion castle: A Byzantine fortress in Asia Minor.

Large and relatively well preserved, the fortress rises in two parts above the modern town and the remains of the palace of the Laskarid Emperors, which lies isolated in the plain.

The lower enceinte encloses a relatively flat area. On its south side, a wall of large, neatly cut spoils covers a rubble core. The towers, where they remain visible, show a different technique: much brick fills the cores. The fragmentary west wall consists of roughly coursed stones and many bricks placed carelessly. A second wall sits immediately behind the south wall, in a very ruined state.

The lower fortress separates from the larger upper enclosure by a dividing wall. That wall exploits natural rocky outcrops and thus appears less substantial. One tower in the upper zone survives in good condition. It has a pentagonal plan. Builders set stones in regular layers and inserted single courses of brick between them. Brick decoration at angles gives the tower a herringbone effect.

The towers and walls of the upper fortress use yet another technique. The coursing here proves rough or absent. Stones mix with bricks and fragments in irregular ways. On the west side, three towers and a gate survive. The gate has a pointed arch, which suggests a Turkish phase when the town continued to flourish. The towers use the same mixed construction.

Dating the Nymphaion fortress: Laskarid architecture and history.

The chronology of the castle’s construction is complex, with the walls reflecting multiple building phases. The lowest sections may date to the Dark Ages, while other parts show clear Turkish influence. The 13th century probably accounts for the wall between the two enclosures and perhaps additional sections. Historical accounts also allow for a partial reconstruction of the building history. The Byzantine historian Pachymeres records that Constantine Porphyrogenitus, son of Michael VIII, built a “tower” in the fortress in 1292. His testimony suggests that this “tower” could refer either to an entire fortress or to a major section of it, though the precise identification of this construction remains uncertain.

Two parts of the castle could fit this description: one is the whole upper fortress, the other is the dividing wall and the pentagonal tower between the lower and upper enceintes.

While certain elements, like a postern with a pointed arch, suggest late phases of construction – maybe turkish – the overall style of the masonry differs from the other walls of the fortress and don´t match the usually rather careful ottoman mansonry – stonework looks rough, and mixed with brick rarely laid in courses. Instead, it resembles Ionian forts, such as Afsar near Miletus or Keçikale above Ephesus and the Cayster Valley, and scholars attributes this construction to the Laskarids.

On the other hand, the pentagonal tower presents regular stone layers, single brick courses, and decorative brickwork strongly resemble the tower of the inner citadel of Smyrna. That tower forms part of the Laskarid rebuilding program. The resemblances suggests that John III Doukas Vatatzes ordered work at Nymphaion as well, and such a program would fit the known historical circumstances.

Yet the decorative quality of the towers at Nymphaion and Smyrna seems higher than at other sites in Lydia and Ionia. That difference raises the possibility of later additions or rebuildings. Scholars note that secure parallels for Palaeologan fortresses in Asia Minor remain scarce, making it difficult to safely attribute construction remains to this period at Nymphaion or elsewhere.

With the current state of knowledge, we can say that the Laskarids, probably under John III, greatly restored and extended fortifications that may have existed since the Dark Ages. In the late 13th century, under the Palaiologans, some additions – such as the tower of Constantine – were made to strengthen the site. After the conquest, the Turks introduced certain adaptations but did not significantly alter the structures.

Nymphaion in the context of Byzantine western Anatolia fortresses

Nymphaion belongs to a wider group of Byzantine fortress sites in Asia Minor, which included major centers such as Smyrna, Magnesia, and Tripolis, as well as secondary strongholds like Asar, Palaeapolis, Maeonia, Satala, and Tabala. Most of these fortifications followed a regional logic established by the Laskarid dynasty. In particular, John III Vatatzes focused on securing western Anatolia and invested in a defensive network designed to protect the main roads and shield the Empire of Nicaea from the neighbouring Turks.

These fortresses were generally simple, utilitarian structures adapted to the terrain in order to reduce construction effort. The division into lower and upper fortifications also appears at Ephesus, Miletus, and Smyrna. Larger sites such as Nymphaion, Smyrna, or Magnesia received more attention, yet none stand out as monumental works of military architecture. Still, they illustrate the defining characteristics of Laskarid military design.

As one of the main imperial residences, Nymphaion formed a key part of this network. It became one of the strongest fortresses in the region and served several times as a base for campaigns against the Turks. This defensive system proved effective for a time. However, the western policy of the Palaiologoi, who shifted troops away to Europe, weakened the Byzantine position. By the early 14th century most of Asia Minor had been lost. Nymphaion, together with Magnesia, was among the last fortresses to fall, in 1315.

Nymphaion stands as a representative example of late Byzantine military architecture in western Anatolia. The site shows repetitive repairs, multiple techniques, and clear Laskarid influence. It shares features with Smyrna, Magnesia, and Triopolis. It also differs from the monumental fortifications of Constantinople. Nymphaion served practical needs: it defended a local district, sheltered an imperial presence, and formed part of a wider Laskarid defensive network. Today its ruins join the corpus of Byzantine fortress Asia Minor studies and help us interpret the pragmatic, regional character of Laskarid architecture and Byzantine western Anatolia fortresses.

Sources.

C. Foss, “Late Byzantine Fortifications in Lydia,” JOB 28 (1979) 309-12, 316-20.

H. Grégoire, Recueil des inscriptions grecques chrétiennes d’Asie Mineure I, Paris, 1922, no. 83; Pachymérès I, 149.