Explore the multiple facets of Byzantine Art

A journey through Byzantium’s artistic legacy

Icons, mosaics, frescoes, illuminated manuscripts, and monumental architecture—these are just a few of the extraordinary achievements of the Byzantine world. Although the empire disappeared nearly six centuries ago, its art continues to resonate, offering insights into a sophisticated culture where faith, politics, and aesthetics were intertwined.From the shimmering mosaics of Constantinople to the intimate beauty of devotional icons, Byzantine artistic traditions shaped not only the Eastern Orthodox world but also the wider European Renaissance that followed.

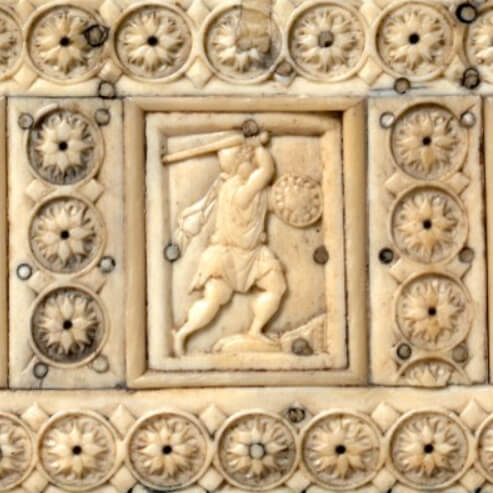

People often think of Byzantine art as purely religious. That view comes from what has survived, mainly works made for churches and devotion. But it is not the full story. Secular art also flourished. It appeared in painting, sculpture, jewelry, and elegant decorative objects. Many works continued classical traditions, inspired by ancient statues that still stood in Constantinople’s public spaces and kept the legacy of antiquity alive.

Most of the secular art masterpieces have been lost to centuries, giving sometimes the impression that Byzantines were all about religion.

Change this vision!

Though very codified, the sacred art has been an incredible space to express the artistic tendancies, struggles of the time and genius of the Byzantine society.

Dive in the art!

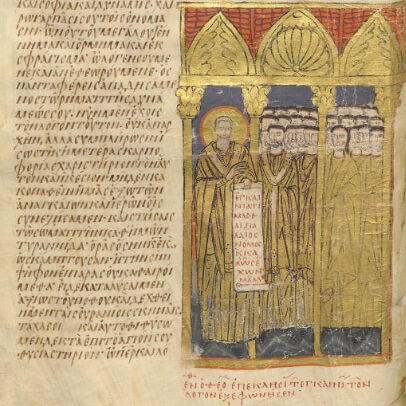

Christian art developed alongside the emerging Christian liturgy and the growing need to visualize faith for new believers. From the 3rd century onward, artists began depicting biblical narratives, saints, and scenes of salvation, often adapting familiar Roman imagery to new religious purposes. These images remained controversial for centuries, shaped by debates over idolatry and worship. Acceptance came only in the 8th century, when John of Damascus articulated a theology of icons that distinguished veneration from worship. After the Iconoclast Controversy ended in 843, images became central to devotion, teaching, and imperial representation, and workshops across the empire thrived.

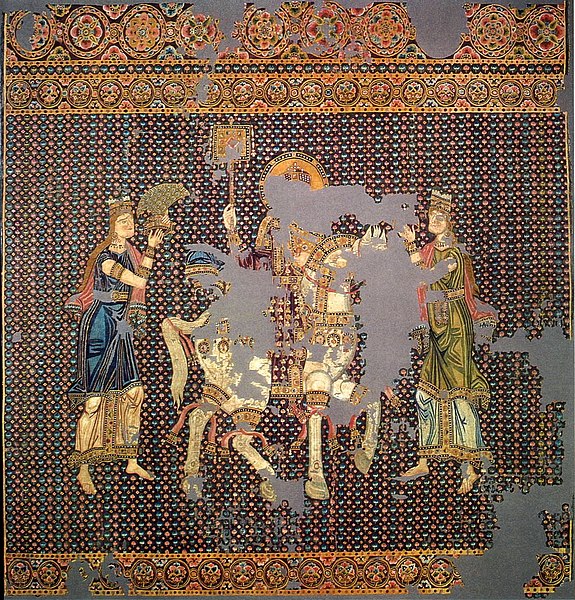

A powerful cultural revival followed, especially in the 10th century, known as the Macedonian Renaissance. Artists revived classical naturalism and early Byzantine splendor, while also developing new ways to express emotion and narrative. Under the Komnenos emperors, Byzantine artistic influence stretched widely: Greek and Armenian masters worked in Russia, the Balkans, and Italy, spreading refined techniques and bold iconography. The Latin occupation of Constantinople in 1204, however, weakened court patronage and forced many artists to relocate to emerging regional centers.

After the reconquest of Constantinople in 1261, the Palaiologos dynasty led a final artistic flowering. Artists embraced expressive figures, refined modeling of light, and elegant spatial compositions, introducing greater psychological depth to sacred scenes. Monasteries and churches commissioned ambitious fresco cycles, while icons became more intimate and poetic. Classical heritage returned with new spiritual intensity. A distinctive feature of this era was the deep, dramatic Palaiologan blue that set figures against a luminous, transcendent space — a fitting symbol for the empire’s last great artistic triumph.