Byzantine Iconoclast Art and Mosaics at Hagia Irene, Constantinople – Istanbul

Located near the Hagia Sophia, the Church of Hagia Irene (Turkish: Aya Irini) is one of the oldest surviving Byzantine churches in Istanbul. Originally founded by Constantine the Great, it was rebuilt by Justinian I following the Nika riots in 532. In 740, an earthquake caused the collapse of the structure, which was subsequently rebuilt and decorated under Emperor Constantine V during a period of intense religious debate over the use of images in worship.

A leading figure of the iconoclast movement, Constantine V (741-775) embedded his religious ideology within Hagia Irene. Despite the passage of centuries, the church interior has preserved several significant elements, including paintings and a mosaic in the semi-apse, providing rare insight into one of the few surviving iconoclast artistic programs. Hagia Irene thus stands as a crucial monument for understanding the cultural history of Constantinople, the development of Byzantine art, and the complex history of Iconoclasm.

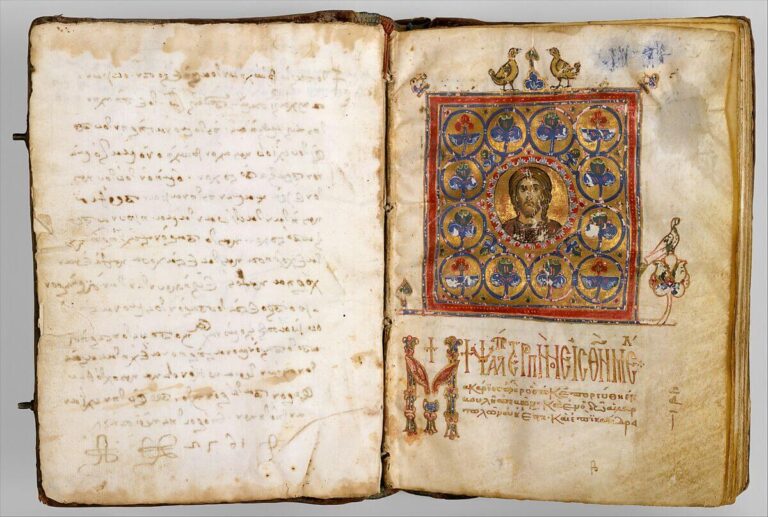

Constantine V, a major figure in the Iconoclast Debate.

Byzantine Iconoclasm (literally “image breaking”) was a theological and political conflict of the 8th and 9th centuries. During this period, the use of religious images was rejected by the iconoclasts and defended by the iconodules, shaping both the art and identity of the Byzantine Empire. Many artworks were destroyed, and figurative representations were often replaced with symbolic motifs. With the final triumph of Orthodoxy in 843, marking the victory of the iconodules, the role of icon veneration and figurative art in Byzantine religious life was finally secured.

Amid these turbulent times, Emperor Constantine V (741-775) emerged as a major proponent of the first wave of Iconoclasm. He linked this religious reform to military victories against the Arabs—successes the empire had not experienced in a century—and aimed to reshape the religious and cultural landscape of Byzantine society while imposing his personal theological views. The devastating earthquake of 740, which destroyed Hagia Irene, struck at a difficult moment for the empire, already weakened by territorial losses, recurring plagues, sieges by the Avars and Arabs, and internal unrest, including the rebellion of the iconophile general Artabasdos, Constantine’s brother-in-law, in 742. Despite these challenges, Constantine crushed the usurpation and reasserted his authority, advancing his political and religious agenda. The reconstruction of Hagia Irene, which appears to have continued until at least 753, also offered an opportunity to embed his ideological vision into the church’s fabric.

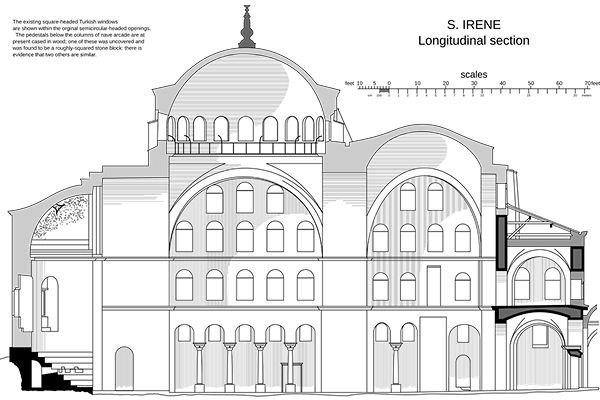

The reconstruction of Hagia Irene after the earthquake of 740.

The rebuilt Hagia Irene followed the plan and scale of its predecessor. Entered through an atrium and narthex at the west, the lower story preserved the basilical layout of the former church. The long nave was divided into two bays, flanked by side aisles and galleries.

Constantine’s architects introduced several key improvements in the superstructure. A novel cross-domed unit was added to the upper story. In the eastern bay, transverse barrel vaults over the galleries supported a dome on pendentives, replacing a weaker structural system that likely contributed to the collapse of Justinian’s church.

The decorative program was likely installed shortly after the Council of Hieria, where bishops endorsed Constantine’s views on image worship, reflecting the core of his theological arguments. Through this artistic program, the emperor sought to communicate his religious positions visually, assert his authority as the church’s patron, and position Hagia Irene within the new ceremonial and liturgical order he was establishing.

The Iconoclast artistic program of Hagia Irene.

The mosaic of the cross in the semi-apse.

Rising above the synthronon and altar, the conch of the slightly pointed apse contains the only preserved mosaic in Hagia Irene, and the most striking statement of Iconoclast art surviving from the Byzantine times. Instead of showing the Virgin and Child, or the Christ Pantocrator, as it had become traditional across Byzantine church decoration, the semi-apse mosaic employed the pre-existing veneration for the True Cross to present a new, iconoclastic vision of the Godhead – a strong, yet resplendent image for contemplation of the divine.

On a golden background, the spare outline of a golden cross, each arm subtly flared at its end. The cross rests on a three-stepped platform, itself set upon a carefully graded green ground, with five bands ranging from light yellow-green to dark blue-green as they ascend. From a distance, these gradations blend into a solid foundation for the platform and cross. Both cross and platform are outlined in black, and their interiors are filled with the same gold-glass tesserae that compose the background.

Almost paradoxically for an art of iconoclasm, the mosaics convey a material, almost tangible cross, hovering in golden space above the altar. The cross appears perfectly straight and perpendicular, yet from close proximity or oblique angles, its true design emerges: the arms curve downward, visually corrected to appear upright when seen from a distance. Lush mosaic foliage frames the cross in double arches.

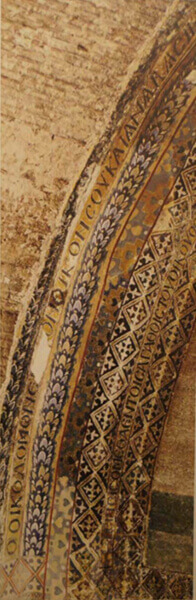

The mosaic inscription on the inner and outer arches.

The inner arch features an abstract geometric pattern of lozenges with fleur-de-lis infill, accompanied by an inscription from Psalm 64:4-5:

“We shall be filled with the good things of thy house; thy temple is holy. (Thou art) wonderful in righteousness. Harken to us, O God our savior, the hope of all the ends of the earth, and of those afar off on the sea.”

The outer arch is framed by dense vegetal wreaths and cites a passage from an apocalyptic doxology in Amos 9:6:

“It is he who builds his ascent up to the sky, and establishes his foundations on the earth; the Lord Almighty is his name.”

The paintings of the aisle vaults.

Echoing early Christian decorative patterns, the aisle vaults were once adorned with lush painted vegetation interwoven with dense geometric motifs, centered on jeweled crosses that may have symbolized the earthly realm beneath the apse’s heavenly image.

Today, only faint fragments of these decorations survive in the south aisle, yet they still offer valuable insight into the type of ornamentation that originally covered the rest of the church.

Visual reflection of Emperor Constantine V´s patronage in Hagia Irene.

Constantine V was not overtly memorialized within the mosaic or painting program of Hagia Irene. Rather than lauding himself as a benefactor, the apse inscriptions exclusively proclaim the name of God. Nevertheless, the emperor made his name and imperial presence visually discernible in other ways. The large Proconnesian marble panels that separated the clerics’ bema from the worshippers’ naos were prominently carved with his monogram, signaling imperial authority.

A highly literate viewer would have noticed that the uncial script used in the apse inscriptions resembles the formal lettering commonly adopted in legal documents—a style previously employed by Justinian in the dedicatory inscription at Hagii Sergios and Bakchos. By placing his monograms alongside those of Justinian and Theodora, which appear on ten capitals of the arcades, Constantine V aligned himself with a distinguished lineage of the church’s noble patrons.

The inscriptions also employ architectural metaphors, referring not to the Crucifixion but to aspects of God’s Temple. They ascribe the act of building to God and employ a wordplay on themelion, signifying both “promise” and “building foundations.” In this way, Constantine modeled his earthly patronage on the divine, asserting himself as God’s representative on earth, where the faithful could be “filled with the good things of Thy house” through the divine service.

Ceremonial role of Hagia Irene in the iconoclast time.

Constantine V was a central figure in the first wave of Byzantine Iconoclasm (726–730 to 797). He recognized the power of ritual in reinforcing both his political and theological authority and skillfully leveraged it. The emperor publicly blinded or humiliated his opponents in the Hippodrome, orchestrated ceremonies marking the birth and death of family members, led an “ecumenical” procession through the streets of the capital, and celebrated the first military triumph the empire had seen in a century.

Constantine V was also fully aware of the power of church ceremony in reinforcing imperial and theological authority. During his reign, reforms were introduced to the liturgical calendar, the order of worship, and likely to the scheduling of major church feasts, even though many of these reforms are first documented in surviving texts from the early 9th century.

Within these ceremonies, Hagia Irene served as a key stational church during Holy Week, commemorating the Death and Resurrection of Christ. On Holy Friday, the offices celebrated there by the emperor and the patriarch combined hymns and scripture with the veneration of the Holy Lance, the relic that pierced Christ’s side at the Crucifixion, beneath the gleaming mosaic image of the Cross. Worshippers gathered in the naos to await the patriarch, who carried the Holy Lance from the imperial palace. After processing through the nave, the patriarch placed the relic on the altar, knelt in adoration, and incensed it. Following the readings, hymns, and profession of faith, the patriarch returned the relic to the palace.

In this ceremonial context, and according to Constantine V’s theological logic, the mosaic functioned primarily as a recollection of the Crucifixion, possessing formal resemblance but no essential identity. Constantine venerated the Cross but denied that its representation contributed to salvation; the mystery of faith could not be contained by material images.

Instead, it was accessed through symbolic interaction: ritual chants, processions, the Eucharist, and the adoration of imperially-sanctioned relics. Nevertheless, the mosaic of the Cross was inevitably perceived as a symbolic object, analogous to representations found on coins, pectoral crosses, and liturgical crosses.

Based on the surviving elements, the decorative program of the Church of Hagia Irene- encompassing mosaics, paintings, and monograms – presents a radically new vision of the ideal Byzantine church. It expresses a visual language that is both theological and imperial, drawing on inspirations from the distant past as well as the contemporary context of Constantine V’s reign.

Sources.

John Freely, Ahmet Cakmak, Byzantine Monuments of Istanbul, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 136–143.

R. Ousterhout, “The Architecture in Iconoclasm”, in Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era (c. 680-850), The Sources. An Annotaded Survey, Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Monographs 7, ed. L. Bruhaker and J. Haldon, Ashgate, 2001, pp. 3-36.

Jordan Pickett, “The apse mosaic of Hagia Eirene: The splendor of Iconoclasm”, in Mosaics of Anatolia: the Square of Civilization, ed. G. Sözen, Istanbul, 2011, pp. 309-320.