Saint Nicholas Byzantine church and monastery in Mesopotam, Albania

Today, the Church of Saint Nicholas stands as the principal surviving monument of a Late Byzantine monastery near the village of Mesopotam, in Northern Epirus, present-day Albania. Probably founded in the 13th century, the monastery was directly dependent on the Patriarchate of Constantinople and served as an important religious and economic center of the region during the 13th and 14th centuries. Its impressive church, with its unusual plan, rich sculptural decoration, and recently uncovered wall paintings, together with scattered remains of the monastic complex, have drawn the attention of scholars. These studies have helped to reconstruct the history of the monastery, otherwise poorly documented in written sources.

The foundation of the monastery, shrouded in obscurity.

In antiquity, the site was already occupied. Research and excavations carried out by the Albanian Heritage Foundation have dated some of the stones to the Hellenistic period, specifically the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. These investigations also confirmed the monument’s connection to Phoenice (modern Finik), the capital of the Epirote League, located about three kilometers from the monastery.

The date of the monastery’s foundation, however, remains debated. While some have proposed an early origin in the 11th century, during the reign of Constantine Monomachos (1042–1055), a later foundation appears more likely. Certain scholars place it around 1224–1225, when the Despotate of Epirus was at its peak, but the archaeological evidence and architectural features point instead to a construction phase between 1272 and 1286. This corresponds to the period when the Angevin kings of Sicily ruled the area between Durrës and Butrint, at the height of their feudal presence, before the Byzantines reclaimed most of the Albanian territories.

Several elements support this hypothesis, first advanced by A. Meksi. The three fleur-de-lis motifs in the narthex floor resemble the Angevin coat of arms. Parallels have also been noted between the floor mosaic of the church and that of the Blachernae church in Arta, as well as between the sculpted reliefs of the outer façade and those of both the Blachernae church and the castle of Arta. According to Meksi, this context also explains why the church possesses a double apse, a unique feature in its type. He suggested that this arrangement allowed the monastery to accommodate both Catholic and Orthodox rites. Ceramic material collected during a 2004 survey further also places the beginning of the monastery’s activity at the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century.

Another scholar, P. L. Vokotopoulos, offered a different interpretation. He argued that the lower part of the structure, built with large rectangular stone blocks—some decorated with reliefs of real or imaginary animals—may belong to an earlier, unfinished building with Romanesque affinities. He attributed the upper masonry, brick decorations, opus sectile floor, and colonnaded portico to the architectural tradition of Arta, drawing comparisons with the churches of Paregoretissa and Kato Panaghia. He sees the church’s extraordinary plan, however, as characteristic of the Despotate of Epirus, whose builders often favored unusual solutions, as seen also in the Paregoretissa church.

Later history of the monastery.

The monastery was stauropegion, meaning that it was directly dependent of the Ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople, thus free from the jurisdiction of the local bishopric. It was an important establishment, as well as an economic center, like the monasteries of the times.

We know from historical records that in the early 14th century, the bishop of the nearby town of Chimara (today Himara) tried to encroach on the monastery and impose its authority. Nevertheless, this was a failure leading to the bishop being expulsed from his see. After John Glykys became Patriarch in 1315, he issued a decree confirming the privileged status of the Mesopotamon monastery.

The study of the ceramics after the 2004 surveys shows a period of destruction, which may be connected with the years 1336–1343. At the same time, other nearby churches, such as that of Saint John near Phoinike and that of Peshkëpi (Nivicë), were also destroyed, while some further away also show a destruction layer with traces of burning from around the same time, such as the monastery of Ballsh or the church of Kafaraj (Fier). These destructions could be connected to the turmoil caused in the region by the campaign launched in 1336 by Andronikos III Palaiologos, with the help of Turkish mercenaries, against the Despotate of Epirus. This invasion was followed in the 1340s by the Serbian advance, which took advantage of Byzantine weakness and civil wars.

Despite this episode which puts an end to the peak time of the monastery, it stayed in use until the beginning of the 19th century. While the ceramic imports came mainly from southern Italy in the late 13th and 14th century, it shifted to norther Italy in the 15th and 16th century, reflecting the growing influence of Venice in the area, before ceasing when the Albanian lands became fully integrated in the Ottoman empire.

In the 20th century, the Saint Nicholas church was one of the 350 churches spared from demolition or conversion into agricultural storage or industrial use under the rule of the communist Albanian leader Enver Hoxha, who commandited the systematic destruction of thousands of religious buildings.

Organisation of the monastic complex of Mesopotam.

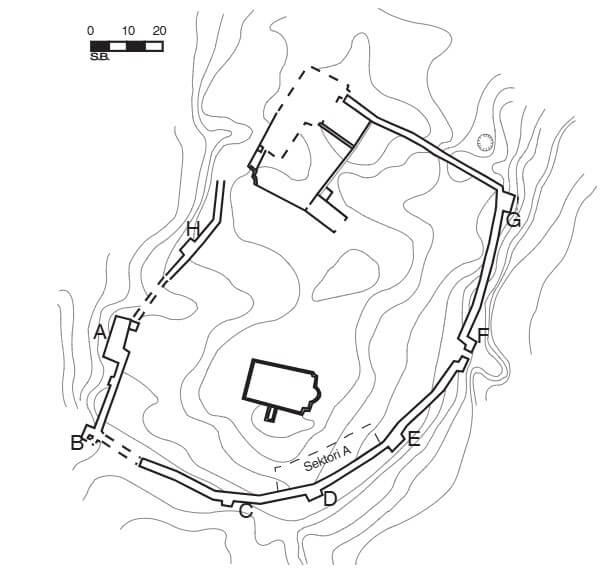

The church and the monastery are located on top of a hill. The complex was protected by a circular wall enclosing an area of about 120 x 80 meters. It was accessible through a gate tower, as was common for Orthodox medieval monasteries, such as Nea Moni in Chios. These fortifications, now only partly preserved, were necessary because the surrounding plain, watered by the river Voustrisa, was completely vulnerable to plundering raids.

The church of Saint Nicholas, which served as the katholikon – the main church – of the monastery, stood at the center of the complex, in front of the main gate, and is well preserved today.

Not much else remains of the monastic complex, but excavations in 2004 uncovered the remains of the monks’ cells. Located near the northern and western sides of the church, their walls were made of limestone. However, their poor state of preservation does not allow a reconstruction of their plan and dimensions. The archaeological material discovered—mainly fragments of roof tiles and pottery, including bowls with green and brown painted decoration under glaze, fragments with sgraffito decoration, and jugs with a yellowish glaze—shows that the monastery and church were used mainly in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The Church of Saint Nicholas and its artistic legacy.

From its foundation, the monastery of Saint Nicholas received an elaborate decoration, much of which is still partly visible today – a clear sign of its importance.

The exterior of the church was richly adorned, and much of its decoration is still visible. The upper brick masonry displays intricate motifs typical of Byzantine architecture. The lower part of the outer walls incorporates decorative reliefs carved in stone blocks, depicting both real and fantastic animals: lions, griffins, eagles, snakes, and other symbolic creatures. Griffins appear particularly often, represented in heraldic positions, frequently facing each other in pairs. In Byzantine art, the griffin symbolized vigilance and divine power. Their presence in this monastic complex highlights not only the ideological and spiritual role of the monastery but also their protective function, as they embodied the idea of spiritual guardianship over the church. Stylistically, some reliefs reveal Western Romanesque influences, while others are closer to Byzantine models. This mixture confirms the multicultural influences at work in the construction of the church, where Byzantine, local Albanian, and Western elements interacted.

In July 2025, frescoes from the Byzantine era were discovered beneath a layer of white plaster at a height of eight meters. They vividly depict saints and may date back to the 13th century. Some features also recall the style of the Palaiologan Renaissance.

Together, the church and the monastery testify to the dynamic cultural life of the region in the 13th century. They stand as monuments of exceptional importance in the history of medieval art and architecture in Albania and the wider Balkans.

Sources:

Daniela Oreni, Integrated Surveying Methodologies for Studying, Preserving and Monitoring the Byzantine Saint Nicholas Monastic Complex.

Skender Bushi, The monastery of Saint Nicholas at Mesopotam (Trial Trenches 2004).

Donald M. Nicol, The Despotate of Epiros 1267-1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, 1984.