The Komnenos mosaic in Hagia Sophia : John II, Irene, Alexios, the Theotokos and Child

The mosaic of John II and his wife Irene of Hungary belongs to the imperial mosaics commissioned by the ruling sovereigns to commemorate themselves and their donations to the Great Church. Realized between 1118 and 1134 in the Hagia Sophia, the cathedral of Constantinople and masterpiece of Byzantine architecture built in the 6th century, it is the only known 12th-century mosaic subsisting in the former Byzantine capital. It was uncovered by Thomas Whittemore between 1935 and 1938.

It is located on the eastern wall of the south gallery of the Great Church, on the second level above the south aisle. This section was reserved traditionally for imperial use during the church services, and was near a doorway connecting Hagia Sophia with the Great Palace, the main imperial residence until the 11th century. The eastern wall is pierced by a window. The mosaic of John and Irene occupies the panel on its right, while the panel on its left hosts another earlier imperial mosaic depicting empress Zoe and her husband(s), dating from the 11th century.

The overall message of both mosaics is the same, emphasizing the continuity of imperial rule despite dynastic change. The earthly rulers are depicted as donors, offering to the divine a bag of money (apokombion) and a document, presumably granting privileges to Hagia Sophia. In both mosaics, the emperors appear on the left and the empresses on the right, and they are shown smaller than the central divine figure.

However, there are some differences. In the left mosaic, Christ Pantokrator occupies the center, while in the right panel, Mary and the Child take the central position. The figures in the Komnenian mosaic are also taller than their counterparts, possibly because they were depicted as overseeing an altar, and a third imperial figure from the same composition appears on the adjacent wall. The lower portions of both mosaic panels are lost, but the older mosaic—depicting Zoe—has survived to a greater extent.

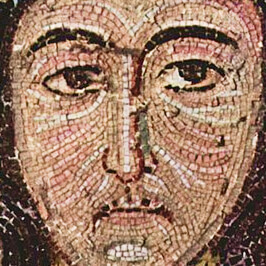

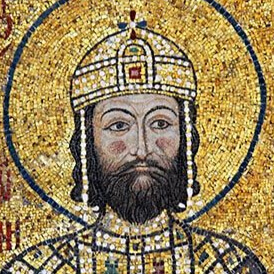

The depiction of Emperor John II Komnenos.

John II Komnenos is represented on the left side of the panel. Son of Alexios Komnenos, he ruled the Byzantine Empire from 1118 to 1143.

The inscription around him reads: “John, in Christ the God, faithful king born in the purple, Autocrat of the Romans, the Komnenos.“

His face has been damaged, possibly intentionally, but one can see that he wears a beard and mid-length hair. He was known for being handsome during his time. His head is surrounded by a halo, a common representation for imperial figures. He is wearing a conical crown adorned with a cross on top and with pearl pendants on the sides. Below, an hypothetical restitution of the emperor face, repairing the damages.

He is also wearing the loros, a long strip of silk cloth embroidered with precious stones, which was draped over the left shoulder and around the waist. Its use was reserved for the emperor and the imperial family for special ceremonies, and was a symbol of imperial power and prestige. It was usually draped over the divetesion, a long silk tunic. John is presenting a bag of money to the Theotokos, for whom he had a particular devotion.

This depiction of the emperor is one of the few surviving portraits contemporary to his reign, making it highly significant.

Another example, a miniature from a 12th-century manuscript, shows the emperor and his son crowned by Christ. John is portrayed similarly, wearing a matching outfit and crown while holding regalia. The consistent rendering of the emperor’s facial features in both representations – including his hair and beard – suggests the existence and circulation of official imperial portraits that artists could use as models to depict the characteristic features of the emperors.

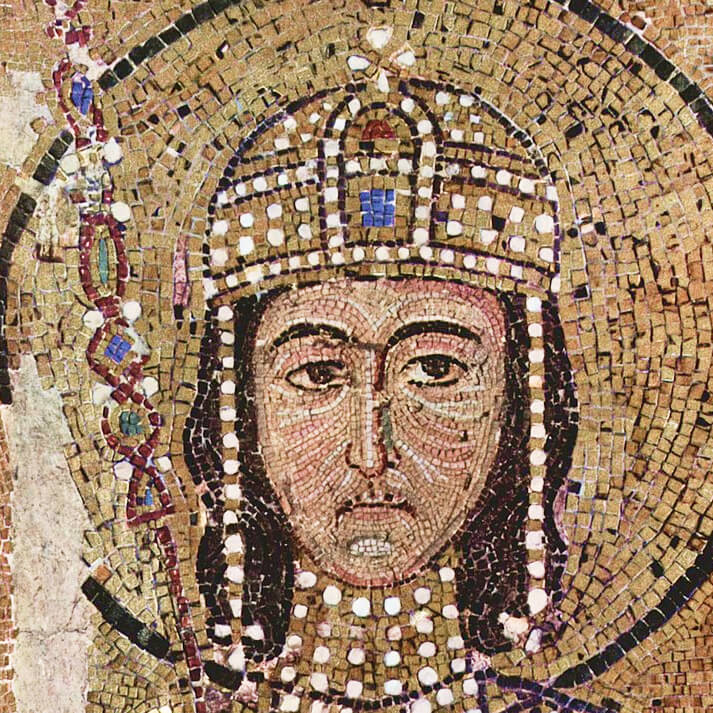

Representation of Empress Irene of Hungary.

Originally named Piroska, Irene was the daughter of Ladislas I of Hungary and Adelaide of Swabia. At the age of 16, she was sent to Constantinople to marry John, and her name was changed to Irene. Together, they had eight children who all survived into adulthood, including the co-emperor Alexios—also depicted in the mosaic—and the future emperor Manuel I.

Irene died in 1134 during an epidemic that struck the Byzantine army in Bithynia. After her death, she was even venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

In the mosaic – the only known portrait of the empress -Irene appears as a fair-skinned lady with distinctly foreign features. Her complexion is noticeably paler than that of her husband, and her long blond hair is styled in two elegant braids.

Her head is framed by a green nimbus and topped with an elaborate gold crown, richly encrusted with large gemstones and pearls. She also wears pear-shaped earrings, completing a regal and refined appearance that emphasizes her imperial status and unique identity.

She is wearing a delmatikon, a female tunic in red silk – one of the luxury products for which Byzantium was famed, mainly crafted in Constantinople and in Thebes, in Boeotia, during the empress’s time. Over this delmatikon, she wears the loros, just like her husband. In her hand, she holds a parchment scroll, similar to Empress Zoe on the adjacent mosaic panel, symbolizing the donations and privileges granted to Hagia Sophia by the imperial couple.

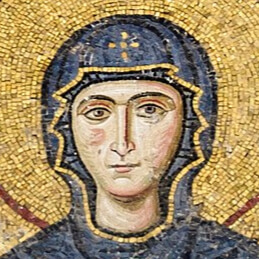

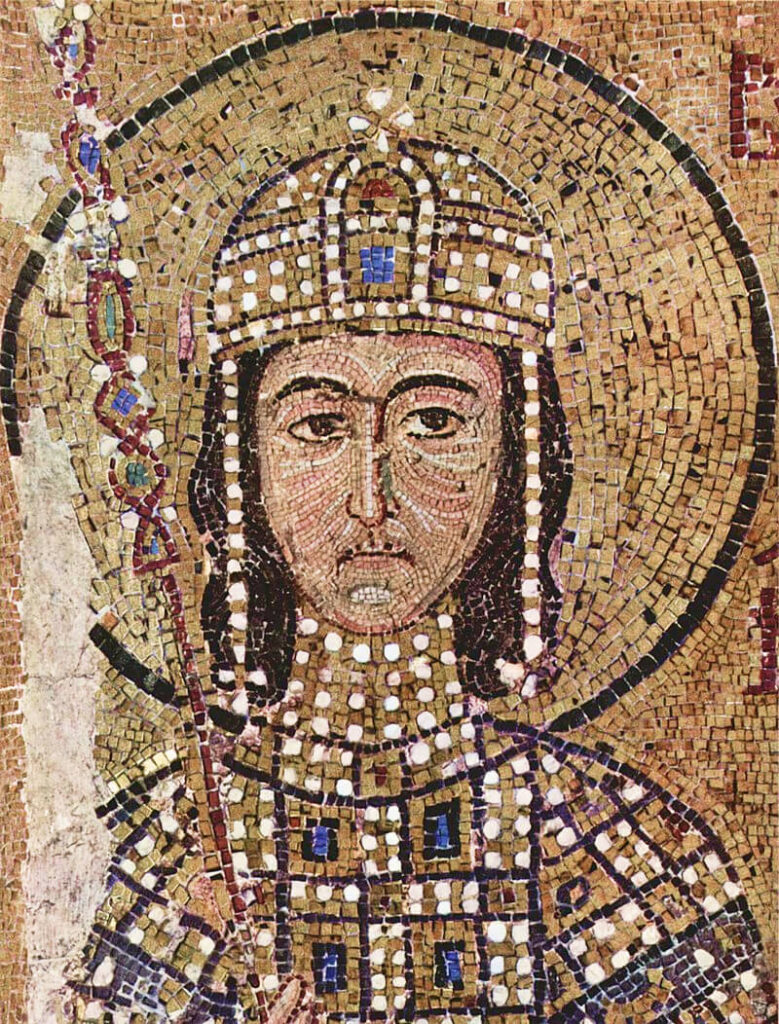

The co-emperor Alexios, son of John and Irene.

Alexios was the eldest son of John and Irene. At the age of 13, in 1119, he was crowned co-emperor. However, he died of disease in 1142, before his father, leaving only one daughter surviving. His younger brother Manuel succeeded their father the following year, in 1143.

On the mosaic panel, located on the wall next to his mother, Alexios is depicted similarly to his father, with long dark hair and a comparable crown and attire. However, he holds a scepter pressed close to his chest.

The artistic rendering of his character appears more relaxed than that of his parents, and his face looks younger – and perhaps, to modern eyes, somewhat wistful. The mosaic emphasizes his youth, showing him with long and thick dark hair and a beardless.

The inscription around him reads: “Alexios, in Christ, faithful Basileus of the Romans, born in the purple.” Alexios is also depicted, crowned by Christ alongside his father, in the 12th-century manuscript mentioned above, which is the only other surviving portrait of him.

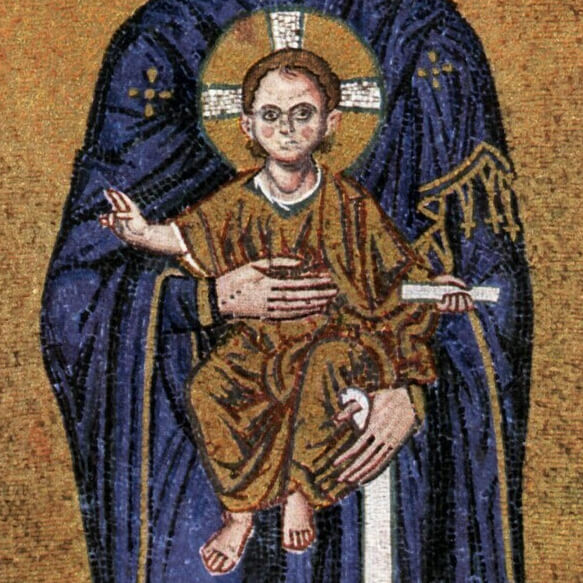

The Theotokos with the Child.

The Theotokos (Mother of God) is depicted at the center of the mosaic panel, holding the child Jesus in her arms. Both are shown frontally, with serene expressions. This type of representation of Mary is called the Hodegetria (“She who guides” or “She who shows the way”) and originates from a famous icon that has been preserved and venerated in the Hodegon Monastery of Constantinople since the 5th century.

The Theotokos was probably depicted on a small pedestal like in many similar representations, making it taller than the imperial characters to show her divinity. She is wearing a blue maphorion, a mantle dress with a hood which was probably close to the typical dress for Byzantine widows or married women in public spaces.

A change of perspective: Some small details of the mosaic.