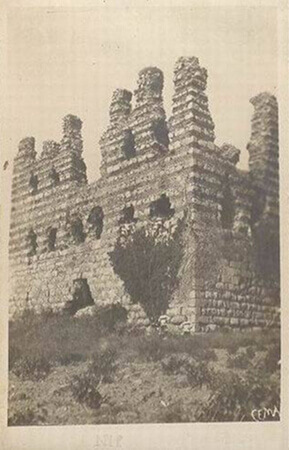

Byzantine Palace of Nymphaion, residence of the Laskarid Emperors of Nicaea

The Byzantine Palace of Nymphaion, located in modern Nif near İzmir, is one of the rare imperial residences to have survived from the Byzantine period. Built and expanded under the Laskarid dynasty, rulers of the Empire of Nicaea (1204–1259), it served as a favored retreat and main winter residence of the emperors. The palace is significant not only as the best-preserved architectural testimony of the Laskarids, but also as a symbol of their efforts to recreate imperial life in exile after the fall of Constantinople to the Fourth Crusade.

With its strategic location outside the city of Nymphaion, the palace also played a major diplomatic role. In 1261, Michael VIII Palaiologos signed the Treaty of Nymphaion here with Genoa, securing naval support for the reconquest of Constantinople. Thanks to this political role and its remarkable survival, the palace stands out as a rare example of secular Byzantine architecture outside Constantinople.

Role of the Palace of Nymphaion for the Emperors of Nicaea

After the fall of Constantinople in 1204, Theodore I Laskaris established the Empire of Nicaea, the strongest of the Byzantine successor states.

The network of Laskarid imperial residences.

For the first time in Byzantine history, imperial power under the Laskarids was not concentrated in a single palace. Instead, it was exercised through regular imperial travel across the empire. Nicaea was the dynasty’s main political and administrative center, seat of the Patriarch, but the emperors relied on several residences. The court moved seasonally between them. Among these, the palace of Nymphaion was the favored winter base and a possible location for the celebration of Easter, while Lampsakos was used in summer, and Pegai hosted the court at other times. Additionally, a neighboring imperial monastery served as a burial site for some members of the imperial family.

We do not know the exact date of construction, but most scholars believe John III Doukas Vatatzes (1222–1254) built it. Located just outside the city of Nymphaion on the main road from Smyrna, the palace stood amid gardens that have long since disappeared.

Historical events at Nymphaion.

Despite limited sources – chiefly the historian Georgios Akropolites – we know that Nymphaion hosted several pivotal moments. John III spent many winters here, and after suffering strokes in Nicaea, he was transported to the palace. His attendants set up tents in its gardens, probably as moving him inside the palace was too inconvenient. The Emperor died in those gardens on November 3, 1254.

Nymphaion was also a place were different emperors were proclaimed : Theodore II in 1254, and Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1259, alongside with his co-emperor John IV Laskaris. Both rulers regularly wintered at the palace.

Nymphaion also became a diplomatic stage: two major treaties were signed there, in 1214 and again in 1261. In addition, the Council of 1234 – first convened in Nicaea to discuss the Union of the Churches – was transferred to the city and assembled in the palace, bringing together both the Orthodox clergy and the papal delegates.

Decline of Nymphaion as an imperial residence.

After Constantinople was reclaimed in 1261, the court naturally returned to the restored capital and the Blachernae Palace. Still, Nymphaion retained importance as a military base against the Turks. Michael VIII came back in 1280 to meet his son Andronikos returning in triumph from a campaign in the Meander Valley that led to the reconquest of Tralles. The same, who had become the emperor Andronikos II, resided in Nymphaion between 1292 and 1294, probably using the old Laskarid palace. The city was finally lost to the Turks in 1315, ending its Byzantine history.

Description of the imperial palace of Nymphaion.

General layout.

The Palace of Nymphaion is still relatively well-preserved. It appears as a simple rectangular block oriented north–south, measuring 11.5 × 25.75 meters. There is no evidence that additional wings were attached. This design follows the block-house type common in late Middle Byzantine palatial architecture. In Constantinople, the Blachernae Palace was built from similar block-houses arranged on terraces. The main surviving building of the complex, Tekfur Sarayi, resembles Nymphaion in plan.

Interestingly, a synod document referred to the building as “the house,” suggesting that contemporaries may have viewed it as a modest residence rather than a grand imperial palace.

Exterior structure and aspect.

The palace originally had four stories, of which three remain. The ground floor is largely filled with rubble, making its plan difficult to analyze. A central entrance, around three meters high, once marked the eastern facade, though its original frame is lost. The ground floor was built of massive cut stones, slightly rounded at the edges and laid without mortar. Eight pilasters supported the structure—four on the east wall and four on the west.

The first floor contained three rooms of roughly equal size and served as the main reception area. Upper floors, similar in plan, were accessed by an exterior monumental staircase. Large windows, symmetrically arranged on each long side, illuminated these levels. The upper floors were constructed using alternating rows of stone and brick, a typical Byzantine technique.

Interior architecture.

Inside, the construction combines stone, brick, and mortar. Vaulting solutions employed brick and mortar, while pilasters and ashlars supported the floors. Arches on the east and west sides indicate a complex vaulting system, with cross vaults and barrel vaults covering central spaces.

The first floor likely housed the throne or imperial seat. Its position above the main eastern entrance, opposite a bifora window opening outward, would have emphasized the ruler’s presence.

Remnants of staircases survive in the northern and western walls, suggesting a two-flight system to reach the upper floors. While the first and second floors were vaulted, the third floor likely had a light wooden roof.

The austere facades are striking: plain geometric surfaces, red and white stripes of brick and stone, and almost no decorative features. This simplicity adds to the modest character of the palace.

A modest palace for a modest dynasty.

Although built as an imperial residence, the palace of Nymphaion lacked many of the features associated with Byzantine palatial grandeur. There were no wings, no atrium, no arcades, no decorative colonnades. Safety, practicality, and modesty defined its design.

This approach fits the Laskarid dynasty’s style of rule, especially that of John III Vatatzes. He was remembered for his frugality and practical governance – famously running a chicken farm and encouraging nobles to engage in agriculture. A later anecdote by Nikephoros Gregoras tells how the empress’s crown was purchased with profits from the farm’s eggs.

The palace’s modest yet functional design reflected the Laskarids’ vision of imperial power: restrained, pragmatic, and suited to an empire in exile.

The Byzantine palace of Nymphaion is more than a surviving ruin. It embodies the resilience of the Byzantine state in exile, the adaptability of the Laskarid dynasty, and a rare glimpse into secular Byzantine architecture. While modest in design, its walls witnessed significant historical events, from imperial proclamations, diplomatic treaties, and the final moments of Emperor John III.

Today, the palace stands as the best-preserved architectural legacy of the Laskarids and one of the few surviving imperial residences from Byzantium. Its survival makes it a vital monument for understanding how Byzantine emperors lived, ruled, and reimagined their empire far from Constantinople.

Sources.

Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, vol. 3, pp. 1505-1506.

Buchwald, Lascarid Architecture, pp. 263-268.

T. Kirova, “Un palazzo ed una casa di eta tardo-bizantina in Asia Minore,” FelRav, 1972, pp. 275-305.